A surprising book gives our side a better account—in the environmentalists-vs.-oil-and-gas debate—than one might expect to see in these oil-unfriendly times.

by Jesse Mullins

The Green and the Black: The Complete Story of the Shale Revolution, the Fight over Fracking, and the Future of Energy, by Gary Sernovitz (St. Martin’s Press, New York), 2016.

Gary Sernovitz’s in-depth examination of the shale revolution, thoroughly researched and thoughtfully presented, fills a need that has too-long gone unfilled. While the author might not make every single declaration that the “black” side of the conflict—the oil and gas friendly side—might desire, he nonetheless devotes enough honest information and narrative to our industry’s true practices and activities that we can feel that our case was made. This is not to say that Sernovitz was out to “defeat” anyone. He has a foot in each camp, so to speak, being both a self-professed liberal in New York and also a financial markets professional whose bailiwick is the oil business, and yet he strives to be objective and balanced and to find understanding—not middle ground, necessarily, but understanding—in those points where it might be possible to find understanding.

So, yes, Sernovitz tries to be even-handed. He expresses some admiration for Josh Fox’s documentary film Gasland—the movie famous, or notorious, for its “flaming faucet” kitchen scene—while still disputing some of its claims and deploring its biases. He states clearly his own belief in climate change, and that in itself presents the greatest inner tension within this book, as he ponders possible solutions to that particular issue. I found that the least-compelling aspect of the book, but then that’s my own bias, that I’m not convinced of the alleged proofs of climate change. Or rather that I’m not convinced that climate change is man-made and is something for which the oil and gas industry is primarily culpable.

Nonetheless, it struck me that Sernovitz might have a chance to reach and enlighten the opponents of oil and gas where other writers might not, or where someone with more entrenched views might not, because he does at least show some sympathies for the the green positions, while so many others in this debate are purely one-sided and hence are probably quickly dismissed.

While it hasn’t been our practice at PBOG to review books, this recent release offers so many touch points for conversation and so much useful analysis that it would be a missed opportunity to pass over it. Sernovitz, a polished and professional writer with, as was noted, a career in oil and gas focused private equity investments, is in many ways the perfect candidate for this kind of treatise. He is a managing director of New York City-based Lime Rock, a private equity firm, and is a novelist with two titles to his credit (Great American Plain and The Contrarians), and he is an essayist and review of some note as well.

The author, who employs a lively style punctuated with humor, has done his homework.

I must admit that I came to this book with an expectation that it would be just another specimen of what H.L. Mencken disdainfully called “the However School of Journalism.” And while it’s true that the author stands in the middle somewhat—and being in the middle is not a place for advocacy—I can’t accuse the author, in the end, of being too pat in his conclusions, which often happens when writers play the middle. There’s more effort put forth here to disclose the ways of oil and gas to the “green” side than there is to expound the environmentalists’ cause to E&P companies. And that’s revealing. Because if it’s not indicative that the writer leans to the “black” position, it at least may indicate that he feels, consciously or unconsciously, that the green crusade knows less of oil’s position than vice versa. At any rate, I felt that Sernovitz’s primary audience is environment-minded greens. And yet I can’t imagine a book more instructive for our side than this one, if understanding the issues and the industry is one’s objective. More, this book is just a great high-level picture of where we are and how we got here.

I came to this book thinking it was a timely and convenient topic—convenient in the sense that we’ve taken too many blows in recent times and just the appearance of a book such as this would provide occasion for rebutting some arguments and airing some needed viewpoints. What I wasn’t prepared for was how penetrating Sernovitz’s analysis of the shale revolution would be. This book is a profound treatment of the tectonic shift that is shale technology. (On the following spread are some selected quotes from the book—presented to give just a brief sampling of the diverse themes Sernovitz treats.)

Some readers may be disappointed that Sernovitz concedes the “green” mantle to the greens. I was surprised that there was no discussion of the thought of individuals such as Alex Epstein, Mark Mathis, or Phelim McAleer—oil-sympathetic activists who stand unwilling to call the green side “green” at all. Mathis, for instance, has contended that fossil fuels are the greenest of all energy sources. To grasp that position, one must factor into the equation two considerations that are too-little considered: one being the tremendous power of fossil fuels (they pack such a wallop) as compared to renewables’ diminutive output, and the other being the seldom-discussed detriments of so-called “clean” renewable energy, which on deeper inspection turns out to have dirty aspects of its own.

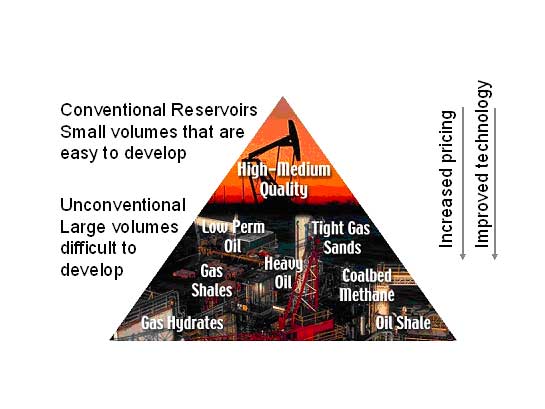

One of the biggest surprises to this reader was the author’s insights into the Resource Triangle and how it has been upended, in a manner of speaking, by the shale revolution. The Resource Triangle is a graphic aid meant to reveal how deposits of fossil fuels vary in economic value according to their respective location and accessibility (and cost of development). Picture a triangle or pyramid marked off in layers from the top point down to the broad base. The uppermost, and smallest, layer represents fossil fuels that generally are accessed earliest, and most easily, by a culture. These are the (often) shallow deposits that are extremely rich and pure—think of oil gushers. These are high yield discoveries, relatively easily tapped, and generally the oil or gas itself is of the highest grade. At the next level down (on the triangle) come deposits that might be deeper, or less accessible, and that are more costly to extract and to refine. At the base of the triangle comes the most hard-to-extract-and-process deposits, which accordingly tend to be of least value in their untapped state, if only because they are less pure and less accessible. But an equally important message of the Resource Triangle is that the further down on the chart one goes, the more PLENTIFUL the resource. Or, as Sernovitz puts it, “the crappier it gets, the more of it you get.”

What Sernovitz points out is that the shale revolution has been a breakthrough that has made those “crappier” rocks into better rocks. And that’s meant that recoverable oil reserves have soared exponentially, because now we’re able to achieve a greater viability down in that more voluminous bottom of the triangle.

Another point Sernovitz makes is that “Shale plays lie beneath where we’ve already discovered oil and gas.” He notes that oil found in that top tier (top of the triangle), which is what we think of as “conventional” oil, such as is found in traps and other geological structures, is oil that migrated there from someplace else. The rock that holds it is not the source rock, per se. The source rock is somewhere else—generally deeper—and is more of that bottom-of-the-triangle resource. But that explains a lot. It explains why unconventional plays underlie conventional plays. It explains the Permian, and it explains the fact that discoveries of large new shale plays are becoming fewer. As the author observes, “There hasn’t been a major new play discovered since the Utica Shale in 2010 and a mid-sized one since the Oklahoma SCOOP play in 2013.”

If I understand Sernovitz correctly, he is saying, in a sense, that unconventional plays are the source rock that fed and created top-of-the-triangle conventional plays. And the latter, of course, are increasingly played out, so the unconventional plays are all the more important. In fact, the author suggests that the word “unconventional” is losing its meaning. The unconventional has become the conventional.

When I was growing up, my dad, an engineer for Texaco, worked the country that is now called the SCOOP play. Texaco worked to extract conventional reserves there, of course. And those had all but played out by the close of the 20th century. In the past few years, when I’ve driven through that country, the rig activity has been striking. But again, it’s a case now of drilling unconventional wells, and it’s a case of “Shale plays lie beneath where we’ve already discovered oil and gas.”

Meanwhile, if it’s true that new shale plays aren’t being found, then it’s also true that, as Sernovitz says, “Most land in the shale revolution has already been leased.” Another weighty pronouncement.

But perhaps the most revealing statement made in The Green and the Black is this one, on the topic of opposition to oil:

“The reason environmentalists have to call the oil industry evil is the only other option they have is to call evil everyone who flies, drives, uses plastics, receives products from anywhere except their own private potato patch. The moment they face the fact that oil and gas companies sell oil and gas because people want to use oil and gas, that there is no separate morality of buying and selling, their entire edifice of propaganda crashes. That’s the moment that terrifies them because that’s when people will stop donating to their organizations. And self-preservation through hate-raised dollars is the whole point of their campaigns anyway…”

That’s when people will stop donating to their organizations. It’s here that our industry has been so unfairly treated. If the issue were simply one of, well, ISSUES, then we could grant, grudgingly perhaps, an unmixed motive to our opponent’s side. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. Maybe the rank and file of oil and gas opposition is sincere (or swayed?) in its opposition, but as Sernovitz implies, the leadership of that opposition does not have unmixed motives. If they’re going to stay in power—if anti-oil politicians or anti-oil nonprofits are going to keep their coffers filled—they’ve got to have a bogeyman against whom to direct the fray. Money won’t keep rolling in if there’s not a crusade to fight, if there’s not a villain to topple. Why give to anyone if there are no troubles on the horizon? And so oil, being a favorite target (as it always has been) also proves to be a revenue source. If the heat can be turned up on oil, the dollars won’t stop flowing to oil’s adversaries, and they’ll stay in office (or grow in size and influence) because they have a lively cause to defend, and they have a “motivated” constituency. It’s that fundraising element (of theirs) that is oil’s greatest dilemma. How to end that? That’s the question for our age.

In demonstration of his point, Sernovitz later offers this:

“And then shale opponents came up with a completely different reason to oppose drilling, one technically much harder to disprove. Leaking [methane leaks] became the new fracking.”

And later, this:

“The 350.org movement argues that the best way to prevent the burning of those reserves is to make it morally unacceptable to extract oil, gas, and coal from the ground.”

As these instances indicate, any defeat for oil’s opponents just raises the need, and triggers the arrival, of a fresh grievance against oil. It’s not enough that oil simply earns money. That was the main accusation decades ago—oil’s “obscene profits.” But as time goes on, it seems that the grievances have to be ever-greater threats. And so the loss of life, or the destruction of the planet, becomes the rallying point. Like a snake that keeps shedding its skin, the opponents of oil must keep shifting their attack as old ploys get disproven or the sky refuses to fall. And that brings us to the latest strategy by oil’s adversaries. The “keep it in the ground” movement.

Sernovitz writes: “The larger tactical, and I think ethical, problem with the divestment campaign is the focus on supply rather than consumption. Drew Gilpin Faust, president of Harvard, put it best when the university declined to divest from fossil fuels: ‘I also find a troubling inconsistency in the notion that, as an investor, we should boycott a whole class of companies at the same time that, as individuals and as a community, we are extensively relying on those companies’ products and services for so much of what we do every day.’”

When it comes to The Green and the Black, it’s all about money. Interesting thing is, it’s about money for the green lobby.