Sean Lobo of Johnson Specialty Tools said it all in a short summation: “Efficiency. It’s all about efficiency.”

His subject was drilling fluids. Specifically, today’s advanced drilling fluids. What goes into making those fluids—and how they’re utilized—is a story that is inextricably linked with the business of, well, drilling itself. And just as the business of drilling is always consumed with efficiency, so is the business of drilling fluids themselves.

But before we get into today’s drilling fluid refinements, let’s review the basics. What are drilling fluids? And what do they do?

We need a definition, and Wikipedia gives us this one:

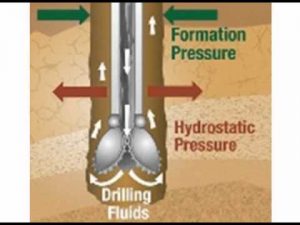

“In geotechnical engineering, drilling fluid, also called drilling mud, is used to aid the drilling of boreholes into the earth. One of the functions of drilling mud is to carry cuttings out of the hole. [Two] main categories of drilling fluids are water-based muds (WBMs), and non-aqueous muds, usually called oil-based muds (OBMs)…. The main functions of drilling fluids include providing hydrostatic pressure to prevent formation fluids from entering into the well bore, keeping the drill bit cool and clean during drilling, carrying out drill cuttings, and suspending the drill cuttings while drilling is paused and when the drilling assembly is brought in and out of the hole. The drilling fluid used for a particular job is selected to avoid formation damage and to limit corrosion.”

Lobo, at Johnson Specialty Tools, said that over the last five to ten years, changes in the realm of drilling fluids have been all about achieving efficiency, whether that efficiency comes from cost savings, from better performance, or from streamlined drilling processes. Lobo’s employer, Brett Johnson, co-founder and CEO of Johnson Specialty Tools, agrees, adding that synthetic drilling fluids are gaining a foothold in the industry.

“There’s still a lot of operators that run their legacy mud programs that they’ve run for decades out here in the Permian,” Johnson said. “But we’ve got a lot of major operators—the Oxys, Chevrons, Diamondbacks, ConocoPhillips, the big, big players out here that are running 10, 20 rigs. Those guys are adopting new mud programs that have synthetic fluids. It’s synthetic mud that maximizes the viscosity downhole.

“They maximize their amount of time they can drill without having to make a bit trip. It’s all about your hole condition downhole. When your hole condition is ideal—and that can happen due to the efficiency of the mud you’re using—it saves you money by not having to change your bit out two, three times a well.”

Johnson said that’s what the majors, and the major independents, are trying to achieve. “You want ideal hole condition for your drilling process. And these newer muds—these synthetic-based muds—do that.”

Within the past decade, developers of drilling fluids have created their synthetic products that have the same viscosities and properties of oil-based muds, but are not made using an diesel oil inversion. (Oil-based muds typically use the mineral barite, along with other additives, to increase the density of the mud and to achieve other properties.) But today various manufacturers, including Newpark Drilling Fluids, are making new synthetic fluids, some of which are called “Pink Muds.”

Said Johnson: “Pink muds give you the same properties as OBM, but they’re cheaper than a diesel-based mud. Yet you get the same properties that allow you to ‘scoot’ and drill downhole as you’re in the lateral section of the well.”

Johnson said that oil-based muds are known for having that benefit. “OBM really comes into play in the lateral sections of horizontal wells. You’re trying to scoot your drilling tools and your systems down through that lateral… [Gravity is of no help once the borehole turns from the vertical and moves horizontally.] And these laterals keep getting longer. You’ve heard of two miles, three miles, and even some going four miles on a lateral. The longer you go, the more crucial the mud is to what you are doing downhole.”

Drilling fluids help to balance the pressure within a borehole when the drilling fluid is pressurized enough to keep formation fluids from entering the borehole This process is illustrated by YouTube video found here: YouTube.com/watch?v=ZoWidsOC6TY

Another factor in drilling mud performance is solids control. Solids control comes down to controlling the so-called “low gravity”

elements. Said Johnson: “They’re trying to minimize the presence of, or amount of, low gravity. Low gravities are rocks or shale the size of a penny up to the size of a quarter. You’re trying to get all that out of your hole and cycle it all out of your mud. That’s very important with drilling today—to take away the wear-and-tear on your bit and all your tools downhole.” So the quality (and makeup) of the drilling mud makes a difference in solids control.

Ken Goldsmith, founder of Midland-based Mudsmith, describes himself as a wholesaler of bulk commodity products to the retail drilling mud companies—those being the personnel who are going to actually use [apply] the technology at the wellsite. Prior to 2015, Mudsmith was involved in that retail end of things. But Goldsmith decided, during that bust year of 2015, to refine his business model. And Mudsmith still offers completion, workover, and kill fluids retail to end-users.

Reached for comment, Goldsmith dismissed the idea that he had anything authoritative to say on drilling fluid activity as it is conducted at the wellsite. That was more of a question for mud engineers or others closer to the drilling activity, he said. Just the same, hearing Goldsmith’s version of how the drilling mud world has changed over time is itself a revealing exercise.

Speaking of his experiences of a decade or so ago, Goldsmith said he had been, at that time, rather reluctant to enter the oil-based mud market on a retail [that is, direct to end-user] basis “because you go from a non-hazardous drilling fluid [water-based mud] to more of a hazardous drilling fluid [oil-based mud.]. That requires, for instance, hazmat truck drivers. And you’ve got to buy millions of dollars’ worth of diesel oil. And the additives are expensive.”

About ten years ago, when the shale boom was beginning to erupt in the Permian Basin, use of oil-based mud was on a steep incline.

“It [OBM] is great during the boom, because you can sell all of it that you can make,” Goldsmith said. “But when the bust comes—and we all know it’s going to come—the mud companies have to take back in hundreds of thousands of barrels of mud on credit. And they may have it sitting in storage tanks for two or three years. Those companies start going broke because they’re renting tanks, and they can’t afford to have all that inventory on hand.”

Even when the boom starts back up, the technology and the product lines may have changed, and mud companies that have held drilling mud in storage for years might find they need to all but give away their mud to oil and gas operators to get rid of that inventory and stock up on what’s new.

Goldsmith said one of the main changes he sees today is that, personnel wise, most of the drilling mud jobs “have gone to camp jobs.”

In other words, the crews are largely living on location. “And they may be brought in from all over the United States, because we have such a labor shortage in the Permian Basin. And so they’re transient workers. The whole countryside is covered up in man camps and that sort of thing. And they’re drilling these wells about as much horizontally as they do vertically [in terms of total footage drilled]. So if they go down 10,000 feet they may go sideways 10,000 feet, or longer. The laterals can be longer. In cases like that, in order to keep the holes clean and stable, and to have good penetration rate, they have [at least until very recently] favored diesel oil-based drilling fluid.”

Goldsmith said that that’s because diesel drilling fluid is simple to run—it’s not as difficult to manage as a water-based drilling fluid.

“Shale will not swell in the presence of diesel like it will in the presence of water, because water hydrates the shale and it can swell. If it swells, it falls apart, and you wind up with hole instability… and getting stuck in the hole… and all those kind of things.

A floor hand pours anti-foaming agent down the drilling string on a drilling rig. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

“So those are the kinds of reasons that they went to diesel based drilling fluids.”

Goldsmith actually said “back to,” because oil-based mud was not precisely a new thing in the Permian in the 2010s. It had been used many years prior. But there came a long layoff (about 25 years) in oil-based mud in this region, so that the re-introduction of it in the past decade or so made it seem like something new.

“Now, however, they’ve done so much of it [OBM], they’re concerned about the environmental impact of diesel, because, as mentioned earlier, it’s a hazardous material. And so some operators have actually gone back to water-based drilling fluid.”

Or to synthetic drilling fluid.

“It’s like a pendulum swinging,” Goldsmith said.

PB Oil and Gas asked Brett Johnson if he, too, had noticed a swing back to water-based drilling fluids.

“Yes,” he said. “Particularly so in the Midland Basin. In the Delaware basin, that is not achievable. But in the Midland Basin, which is the legacy basin of the Permian, a lot of these big operators like Pioneer and Diamondback, who have the largest presence in the Midland Basin, are getting anywhere between 60 and 80 percent water-based drilling only on all their rigs now.

And that is a hundred percent a cost deal. They’re only doing that to try to save costs.”

Johnson Special Tools (Brett’s company) offers a product and service to help operators make water-based mud work for them in these environments. For more on that, see the related item (Going with the Flow).

Speaking of what can be done today with water-based mud, Johnson said this:

Johnson Specialty Tools also rents equipment. Here is one of their mud vacuums (foreground) at the foot of a drilling rig.

“In a nutshell, if I’m going to go 100 percent water-based drilling in the Midland Basin for [say] Diamondback, in order to go through the lateral process and drill a two-mile lateral, and be as close to [the performance of] oil-based mud as I can, I’ve got to have a really high efficiency water-based mud program. So, if I give away [get away from] oil-based mud, I can’t lose drill time. Because my company doesn’t want me to lose three days of drilling or four days of drilling, or even five days of drilling. I don’t want to add five days of drilling to save, I don’t know, $00,000-400,000 worth of oil-based mud. So you want to keep the same drill time, same efficiency, same wear-and-tear on your tools, but keep it water-based. So in order to do that, you got to be able to maximize your efficiency on location while you’re mixing mud. You have to mix and emulsify the mud fluid at a rapid enough rate to get it downhole at the same pace [as the drilling process requires it, without losing drill time].

From there Johnson went into innovations in the mixing of water-based mud, some of which is described in the accompanying item (Going with the Flow.) Other companies are coming up with their own variations on this theme.

For the Long Haul

Whatever might be the next direction(s) for the drilling fluids industry, one direction for certain is that it is going UP. Globally at least.

The global drilling fluids market, which in 2021 was pegged at $6.1 billion in value, is expected to grow at a Cumulative Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 7.8 percent to reach $12.9 billion by 2031, according to ResearchAndMarkets.com.

Increased research and development activities are underway to develop more efficient drilling fluids while reducing the cost. The shift toward the usage of water-based drilling fluids is due to WBM’s environment friendly and cost-effective nature, Research and Markets said. And the onshore industry is the main driver for change in this sector, according to the source.

“Efficiency. It’s all about efficiency.”

By Jesse Mullins