In Memphis, Elvis is The King.

In the Permian Basin, Oil is The King.

Oil’s had a long string of hits in West Texas, dating back more than 100 years. Its backup singers, natural gas and natural gas liquids, have their place, but they’ll never be the star of the show.

In fact, NGLs are almost completely in the shadows, reaching only about 10 percent of the production levels of oil itself. In January 2021, the most recent figures available at this writing, EIA figures showed NGLs/HGLs accounting for almost a third of liquids production in the United States (5.2 million barrels per day for NGLs out of 16.3 million barrels total).

Natural gas liquids, part of what EIA labels hydrocarbon gas liquids, are themselves actually a quintet. Ethane, propane, normal butane, isobutene and natural gasoline (or Naphtha), in descending order of quantities, are the mix. Ethane is a kind of divider, sometimes found as a liquid in oil or as a gas in natural gas. All of them can be condensed into liquids fairly easily, either by cooling or compressing.

And all of these come out of the ground in fixed amounts, unlike petroleum products such as gasoline, kerosene and diesel, which can be varied by process at the refinery. Ethane, used as feedstock in petrochemicals and in other ways, is about the only one with any options. When its price is high, it’s removed at a processing plant and sold separately. When the price drops, it’s mixed in with natural gas and sold into the gas pipeline.

Propane, used domestically and internationally for heating and cooking, as well as for vehicle fuel, is also refined into propylene, ethylene, and other olefin feedstocks for plastics, synthetic fibers, and more.

As U.S. domestic production of oil and gas grew under the shale revolution, so did NGLs. Unlike oil and gas, most NGLs are not stored. They are instead processed and used domestically as feedstocks for plastics and other materials, or exported. Propane is the exception because of its use in heating.

The Permian Basin’s Role

Because NGLs come from both oil (associated) and gas (non-associated), NGL numbers are related to both. In 2019, U.S. production prior to 2020 averaged 11.8 million barrels per day, but in 2020 dropped to 10.8 million. International research firm IHS Markit predicts a small 2021 uptick to about 11.0 million barrels per day, according to Darryl Rogers, who is the firm’s vice president / midstream oil and NGL.

The Permian Basin, on the other hand, is expected to grow its daily natural gas production from 10.6 bcf/day in 2020 to 11.6 bcf/day in 2021. This will also effectively raise NGL production.

NGL production in 2020 was approximately 1.69 million barrels per day and is expected to rise to 1.72 million bpd in 2021.

Why the greater increase in gas as opposed to oil? Two reasons, says Rogers.

“One is less flaring,” he said. Second, wells that were restarted after having been shut in during the downturn tend to have a higher gas-to-oil ratio than uninterrupted wells. Also, an increase in gas-to-oil ratio is a natural progression in most unconventionals anyway.

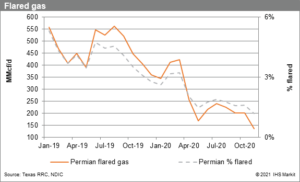

Flaring of produced gas had become almost a crisis in the Permian in recent years as pipeline backlogs had meant producers either had to shut in oil wells or flare the produced gas. Some experts estimated that, at the height of flaring, the Permian alone was burning enough gas to produce electricity for every home in the state—every day of the year.

New pipelines combined with oil well shut-ins have altered that scenario. “Through much of 2019, Permian flaring moved around from month to month but on average it was around .5 bcf per day,” said Rogers. By Q1 2020, producers were reducing flaring. By Q4 2020, flaring was slashed to .15 bcf per day.

An accompanying graph shows that a smaller percentage of gas was being flared, dropping from 5 percent to between 1 and 2 percent of production. “That was a wellhead stream, so it had NGLs in it,” Rogers pointed out. “So we gained 56,000 barrels per day” of NGLs that had previously been flared. “If you think about the added value, it’s roughly a half a million dollars. So they created value in a period when demand was clearly down.” Thus producers made up for some of the oil losses because demand and pricing for NGLs continued strong for the most part.

Any gas produced from an oil-first well must be processed to remove NGLs before being sent to a pipeline.

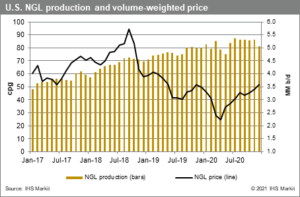

During the depths of the pandemic shutdowns, even NGL prices dropped some—from a volume-weighted price of .52 per gallon in November of 2019 to .25 per gallon during the depths of the pandemic. U.S. production volumes dropped from 5.2 million barrels per day to 4.7 million barrels per day.

“The recovery on the NGL side was much faster from a price and a volume perspective as compared to gas and oil,” said Rogers. “NGLs came back and surpassed the previous peak in July [in production levels] of 2020.”

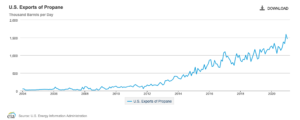

Propane as an Export

With the growth in oil and gas production since 2012, U.S. exports of propane have exploded, reaching 1.6 million barrels per day in December of 2021 (the most recent EIA figures) The numbers began to rise from 2012 on. In January of that year, the U.S. exported 164,000 bbl/day.

Recent months have seen Japan, Mexico, and South Korea as the top propane recipients, supplanting China after the trade wars of 2017 under the Trump administration. U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Warren Wilczewski explained the thinking behind import decisions for most countries.

“A lot of that has to do with domestic policy on the part of the importing country,” he said. “Japan, for example, has a very particular policy for de-risking its sources of energy supply.” The wider they can diversify their sources of energy, from uranium to fossil fuels, the less they have to worry about supplies being cut off. As the U.S. has ramped up exports of both propane and LNG, Japan has seen the benefit of adding a stable source of inflow.

“This is vitally important for importers because de-risking their supply allows them also to hold less inventory on hand in case of a supply disruption. If they are reliant on one supplier for a particular commodity, they are required to hold much more reserve than when they can diversify and pull cargoes from various locations.

Japan was not always the biggest recipient of U.S. propane exports. “China has been number one. For a short time in late 2015 and early 2016 China had the pole position in terms of imports that were exported from the United States,” Wilczewski noted. “They were, in fact, growing until there was a trade disagreement, and China imposed draconian tariffs on imports of propane, butane, and a number of other energy commodities.” With the resolution of the dispute late in the Trump administration, the government began allowing exemptions to the tariffs, and imports began to rise, although not yet to previous levels.

No Crash for NGLs Because People were Still Buying Plastics

When the WTI price went negative in April of 2020 due to a huge demand drop and resulting storage glut, no such thing happened to NGLs, Wilczewski said.

For these commodities, “The starting point for inventories was relatively low, because the impacts of COVID-19 mitigation measures that created the demand destruction of that time occurred near the end of the heating season,” he said. At that time, due primarily to the seasonal nature of propane and butanes demand, inventories are at their lowest point and are starting to grow anyway.

“There was plenty of space in those caverns that could be filled with product,” he said. The only question was, would it refill faster than usual? That would depend on whether demand destruction continued through the beginning of the 2020 heating season in October.

“The fact of the matter was that demand for propane, butane, and ethane was much stronger than demand for transportation fuels.” Though people stopped driving and flying, they continued heating their homes and cooking, with little abatement.

Also, “They were still consuming the products that are made from these NGL feedstocks” and the petrochemicals derived from them. “That demand did not subside. In fact, in many ways, it increased relative to where you would expect it to be,” especially compared to the marketplace as a whole.

Shifting to work at home required people to buy or upgrade computers, monitors, office chairs, smart devices, and other goods made with plastics that come from NGL feedstocks. This is not to mention PPE such as N-95 masks, made with polypropylene, which often is produced directly from propane.

Where Does It Go Domestically?

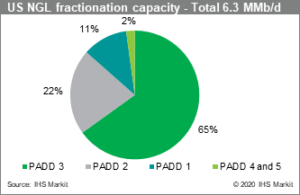

Wilczewski noted that most U.S. NGL processing happens in plants around Mont Belvieu, near Houston, and that most of the plant expansions in the last few years have broken ground there. But Corpus Christi and nearby Sweeny have also grown, as have plants in the Midcontinent (Oklahoma and Kansas). Corpus is adding export capacity for all phases of petroleum and refined products on a regular basis, and there are pipelines connecting Mont Belvieu to industrial sites and export terminals up and down the coast.

With natural gas production growth in the east, in the Utica and Marcellus shale plays, fractionation capacity is ramping up there as well. “In the past six years or so we have seen an emerging hub in Appalachia, where there are two major fractionation centers and a couple of smaller ones in the Appalachian Basin on either side of the Ohio River in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.”

What’s Next for NGLs?

While the main focus is always on propane and ethane because of their volume and, for propane, its use in home heating, the other NGLs have their place. “They’re all important because the butanes and the natural gasolines are easier to manage. But ethane and propane are a little different,” Rogers said.

“Ethan e is used as either a fuel or a feedstock.” He noted that in past years when oil prices were expected to rise into the $70-$80 per barrel range, investors were excited about building ethylene plants that would process U.S.-produced ethane. “But when we have lower crude oil prices, the decision gets to be very murky,” Rogers explained. “We have it available, but with crude being a lower price, the other alternatives—propane or light naphtha, as a feedstock—the ethane advantage is not as significant as in the past, due to global markets.”

e is used as either a fuel or a feedstock.” He noted that in past years when oil prices were expected to rise into the $70-$80 per barrel range, investors were excited about building ethylene plants that would process U.S.-produced ethane. “But when we have lower crude oil prices, the decision gets to be very murky,” Rogers explained. “We have it available, but with crude being a lower price, the other alternatives—propane or light naphtha, as a feedstock—the ethane advantage is not as significant as in the past, due to global markets.”

This year, the propane market is much tighter than usual, Rogers said, so prices will be higher. The  propane winter market starts earlier than it does for natural gas, because the agriculture sector makes huge autumn draws for crop drying. “So the concern is, going into next winter, availability, possibly for crop drying in the ag season, could be tight.”

propane winter market starts earlier than it does for natural gas, because the agriculture sector makes huge autumn draws for crop drying. “So the concern is, going into next winter, availability, possibly for crop drying in the ag season, could be tight.”

The industry usually waits to buy propane until right before it’s needed in the fall, which can create logistics problems along with price issues as demand shoots up. “Last year at peak season we reached 100 million barrels of storage. This year we only expect to reach 88 million barrels. So this year they may have to start building inventory faster if they can,” Rogers said.

But overall there should be plenty of NGLs to go around in the near future.

“We don’t see, over the next year or two, dislocations in the supply chain. We’ve got plenty of NGL fractionation capacity; from the gas processing plant where you have the C3-plus stream to get it to the fractionation center, there’s plenty of pipe.” In previous years when production was growing, “we pre-built a lot of pipe to be supportive of the Permian and other basins continuing to expand. Now we’re going a bit sideways, so there’s plenty of capacity.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in the oil and gas sector. His email address is fittoprint414@gmail.com.