It’s famine to feast. With the return to activity, sandmen are no longer asleep at the wheel. Frac sand companies are hiring people, buying equipment, and gaining market share. Meanwhile, sand itself—as used by E&P companies—has changed.

By Paul Wiseman

Most of 2016 was a crisis in much of the oil industry, and the frac sand sector was no different. Layoffs and red ink were more prevalent than jackrabbits in most sand mining regions, in Texas and in Wisconsin.

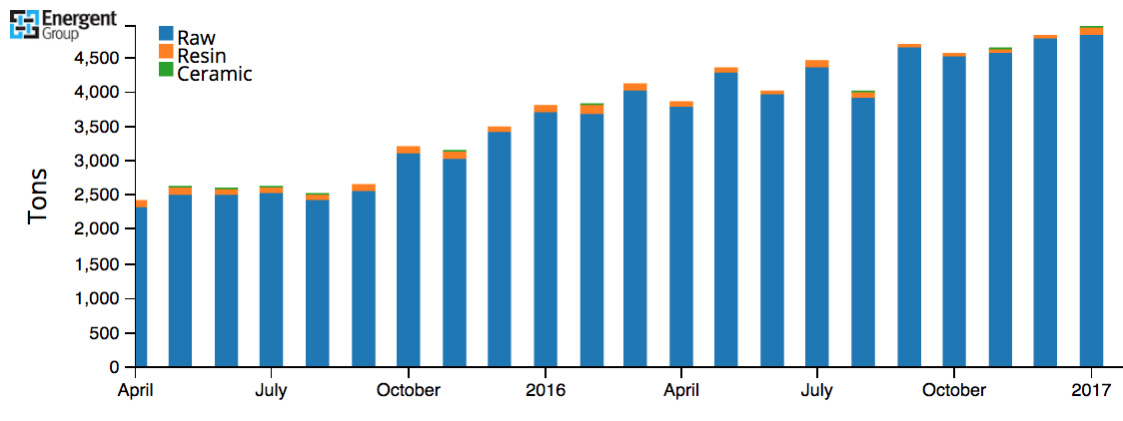

In November of 2016, however, there was a perfect sandstorm, if you will. OPEC decided to cut production and, in turn, raise prices, a move which served to boost drilling and completion activity. About the same time, producers decided to almost double the amount of sand used in most frac jobs, from 2,500 tons to 4,500 tons on average, said Todd Bush, principal, Energent Group. Energent is an oil and gas research group focusing on tracking and analyzing shale activity. As part of that they track the entire supply chain for frac sand and all types of proppant.

It was stability in oil prices as much as the increase that fueled the uptick, Bush said. “Seeing that it’s going to be at and around $50 a barrel, you could have at least some confidence in the action plans of E&P companies going into 2017.”

While many analysts expected the first signs of recovery to involve the completion of DUCs (drilled, uncompleted) wells, there’s actually a mix. Bush said he’s seen a drawdown in DUCs for E&Ps like Concho Resources, but it seems to vary by company as to whether DUCs or new completions take the lead.

Ruben Garza, owner of Arepet Frac Sand, which distributes Texas-mined sand across Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico oil fields, agreed that the uptick started in the fourth quarter of 2016. It gained steam almost too quickly from there. “The sand market has gotten very, very tight, very active” in February and March of 2017, he said. “It started off gradually and now it’s at full speed.”

Producing that much sand is one thing—getting it to the frac site is another. “We feel that one of the constraints is going to be in the trucking factor. We feel that there’s going to be a trucking constraint towards the latter part of this year.” To relieve that situation, they plan to buy more trucks and trailers for the “last mile” deliveries.

Garza added a third element to the speeding up of the frac business—multi pad drilling. Before the bust forced so many economizations, companies would take five days to drill a well then five more days to move the drilling rig. This would effectively allow 10 days for the frac process, including sand delivery.

Now it’s different. “Doing multi-well pads, have a fleet of trucks and you occupy them 4-5 weeks straight because they [the rigs] don’t have to move anymore,” he said. Plus, as Bush stated, each well is using 30-40 percent more sand.

Another squeeze to the industry will be DOT-mandated logging of trucks, which will very strictly limit a driver’s hours per day on the road. This will require not only more trucks, but more drivers.

For the last mile companies (those who transport sand, especially that from out of state, from a rail offload site to the well) to maximize efficiency, they must shorten their trips. Garza said they will want the offload site to be within 100 miles or less of the well, so each truck can make more trips.

To put this in perspective, one well can require 400-600 loads of frac sand. Shortening those trips by even a few miles can pay off greatly in efficiency.

These realities are also changing how suppliers and end users relate to each other. “I think everyone is starting to pick their dance partners, so to speak,” Garza said. This would have been very unusual in the past. “They’re joining a pool of trucks and drivers to follow a fleet. That way you know you’ve secured that amount of equipment for that fleet that’s drilling. It’s becoming a common practice in the industry now.”

End use has changed over the last couple of years as well. A few years ago, Garza said, finer and rounder sand was the choice of the day. Most of that had to be hauled in from Wisconsin and Illinois.

But today, completion crews feel that more is better regarding the amount of frac sand in a formation—so the finer Texas sands from places like McCulloch County (Brady and Mason) are becoming more popular. This is also a boon economically because more than half the cost of Wisconsin sand is found in the railroad costs. Finer sand also can be pumped into the formation up to twice as fast as the coarser variety.

Finer sand also requires less guar and other additives, bringing further savings to operators.

Some producers in the Permian Basin have used the 40-70 and 100 mesh sand all along, said Brett Nix of Erna Frac Sand. Erna is based in Mason.

“We have seen an uptick in interest in 40-70 and 100 mesh over the years. In the last two years there seems to be just an overall increase in volume in frac jobs,” Nix said. He agreed that multi-well pads and faster completions has been an important part of his clients’ increased orders.

Nix added that the above-mentioned sizes are basically all Erna makes, so that’s what they’re going to sell.

Todd Bush points out that availability indeed dictates demand. “More companies will use some of the other types and mesh sizes, but 40-70 and 100 mesh continue to be the largest amounts consumed,” he said.

Fracturing on this large scale is still relatively new, and Bush feels that mesh size preferences have changed as completion engineers learn more about formations and about the effectiveness of various frac techniques.

Sand preferences vary from basin to basin, with 100 mesh quickly gaining ground in the Delaware, while the Midland Basin is slower to move that direction.

Sand companies scramble to keep up with trends—Bush quoted an industry saying that, “Yesterday’s perfect product is today’s waste.” He added, “It’s really hard for them to retool and go through the different production process” to get varying mesh sizes.

Some fracturing methods change with prices, as well. With the downturn in oil prices in 2015-16, sand prices dropped as well. Nix feels that this lower price encouraged completions teams to try increasing the sand in a formation. They soon saw “favorable results from the increased intensity and volume of sand.”

He noted that Erna was not hit as hard as some other frac sand companies during the downturn—partly because of the previously noted shift away from Wisconsin sand and toward the Texas variety.

Erna is using the business boom to add hours to help current employees. During the downturn they cut hours instead of instituting layoffs, so more employees could keep their jobs.

They’re also catching up on equipment repairs, made possible by greater cash flow.

Just as the price of sand (and everything oil-service related) goes down in a bust, there have been reports of sand price increases in some areas. Bush said he hasn’t seen major changes yet. But some end users are protecting their prices by signing long-term contracts with sand providers in order to maintain stability.

Sand, like oil and gas, would seem to be in finite supply. Nix says his company’s mine has about a 25-year life span. Recent reports have told of plans for developing a new mine near Kosse in central Texas and another west of Odessa, and others elsewhere.

With the explosion in hydraulic fracturing in shale play over the last 10 years, this commodity has come from nowhere to be a major player in the energy business. It will be interesting to see what part it continues to play.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in Midland.

Subscribe to receive PBOG delivered to your front door.

[maxbutton id=”15″]

Sign-up for PBOG email updates.