When the time comes to ramp back up, which Texas shale formations stand ready for recovery?

By J. Chase Beakley

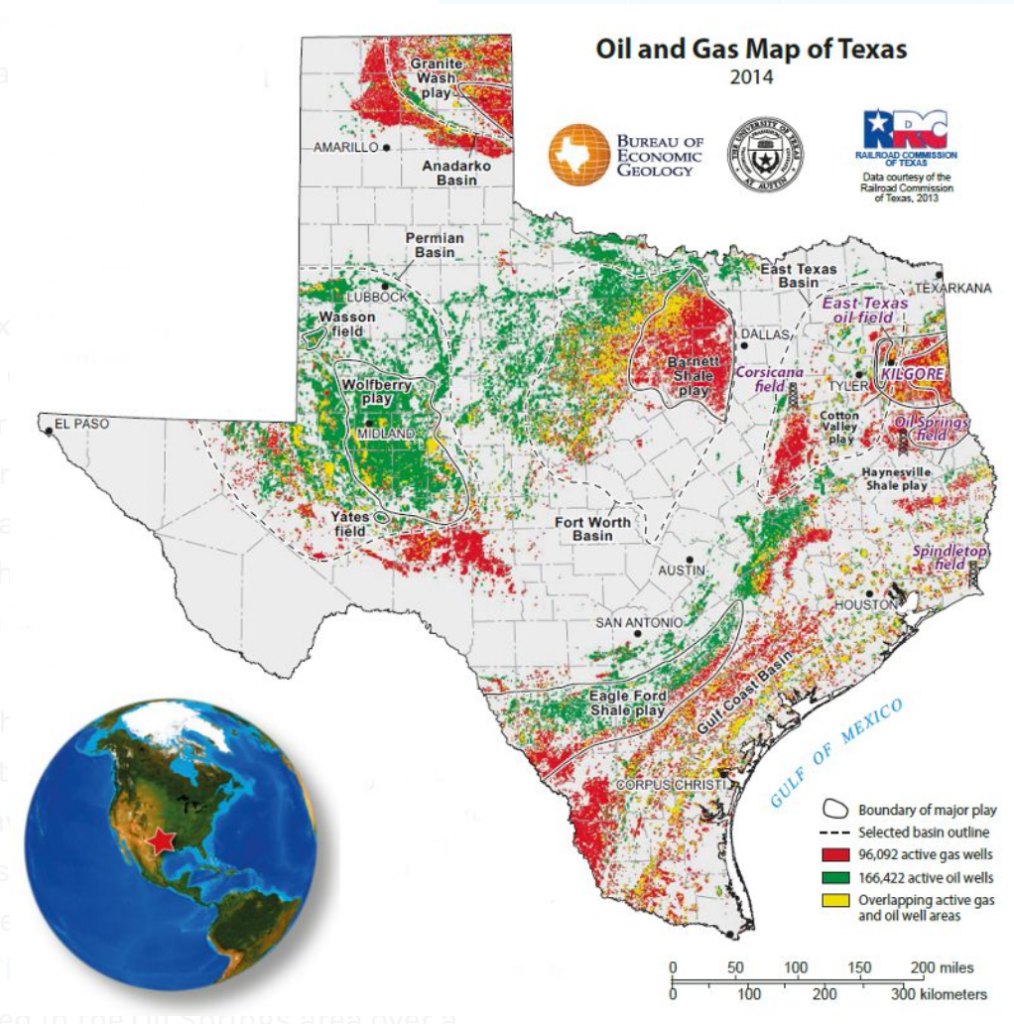

The energy industry has long been the beating heart of the Texas economy, and although the Lone Star State has diversified significantly of late, so many Texans are still entwined in oil and gas. The gravitational pull of the industry throughout the state is of course the result of the sheer amount of money it generates, but another factor that has helped make oil and gas a big part of Texas’ economic DNA is the diversity of plays throughout the state. In Texas we don’t all draw from a single source, as North Dakota does from the Bakken or Pennsylvania from the Marcellus, and the producing regions are spread evenly across the state’s geography. In addition to the economy of the plays, the diversity of drilling opportunities in Texas and the existence of infrastructure to support those opportunities is a major reason Texas is the top producing state in the United States.

As the horizontal drilling revolution hit and unconventional plays took center stage, Texas drilling began to rotate around three axes: The Barnett shale in North Texas, the Eagle Ford shale in the south, and the Permian Basin in the west. Now that we’ve weathered one of the most dramatic price collapses in history, drillers in the Lone Star State are looking to see how each region stands as we await a steady price recovery. In oil and gas, things can change dramatically and instantaneously, and it remains to be seen what mark this downturn will have left on each play.

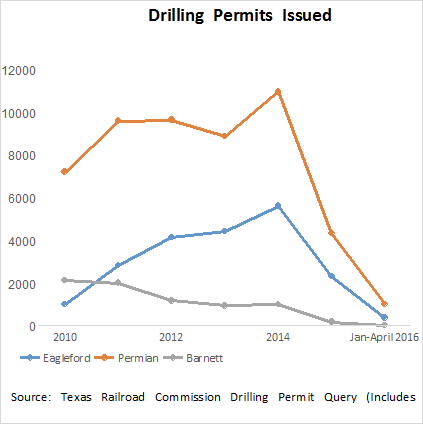

The Barnett shale is a perfect example of how fast a producing region can become irrelevant. Less than a decade ago the Barnett could see 200 rigs working in a week, but in April of 2016, with natural gas prices down around the floor, the Barnett shut down completely. For the first time in years, there were zero active rigs in the entire play.

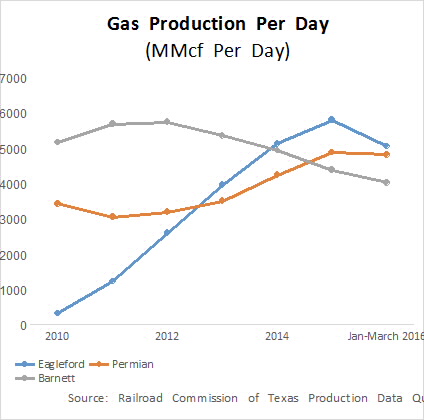

Bob Williams, director of news and analysis for DataWright, which is responsible for the RigData reports and LandRig newsletters, watched the Barnett’s demise firsthand and offered a grim prognosis. “It’s dead, but it had been winding down for a long time before that. Non-core area liquids kept it going longer than the true heart of the play would have merited.” Almost entirely a gas play and once the leading LNG region in Texas, recent numbers from the RRC show that the Barnett was eclipsed in gas production by both the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford shale as far back as late 2013.

The Barnett suffered from plummeting LNG prices and the rise of more economic opportunities in the Marcellus and Haynesville shales. “The Barnett was the grandaddy of them all, but the fact is the sweet spots have been picked over and the nearby Haynesville is much more prolific,” said Williams. “It would take a sustained natural gas price north of $5/mcf to get double digit rigs in there again.” Unfortunately, the global LNG supply has ballooned of late and sources around the world have grown increasingly more competitive with the U.S. producers, making gas likely to get even cheaper in the long run. Barring a major supply snafu, it’s unlikely that the Barnett will ever return to its former glory.

It’s unclear how operators that previously worked in the Barnett will adjust, although capex on the aggregate seems to be siphoned off towards the Haynesville or redirected towards more lucrative oil projects. Luckily, Texas still encompasses two of the best unconventional oil plays in the country.

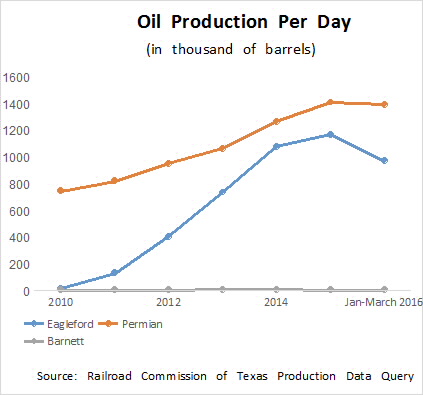

Anyway you count it, the Eagle Ford and Permian Basin shale plays are among the top five most productive regions in the United States, with the Bakken and Anadarko-Woodford rounding out the list. During the 2010-2014 up cycle, both areas saw a surge in productivity, but even when prices collapsed, both regions remained highly productive, despite the fact that there were very few new permits being issued.

Of course, hedging and the demands of operators’ balance sheets were partly responsible for the sustained production, but the consistency also shows that oil can be produced in both places despite dramatic price constraints. Surely, that bodes well for a potential rebound and for investment in the future.

So given that both the Eagle Ford and the Permian are well equipped to seize on a price recovery, where would you rather be to catch the next up cycle? Kirk Edwards of Latigo Petroleum says the Permian is still the place to be. “The Eagle Ford is in the top five in the U.S. so we don’t need to feel sorry for it, but of course you’d rather be in the Permian,” said Edwards. “It’s shallower, the fracs are smaller, and it has location, location, location. The Permian was the last to shut down and it’s always the first to come back.”

A laundry list of perks makes the Permian Basin the reigning champ of the Texas shale plays. First of all, extensive infrastructure minimizes transportation costs compared to more remote producing regions. The Bakken, for example, needs much higher crude prices to offset the transportation costs required to get the product from the frozen plains of North Dakota down to the refineries, and in the Eagle Ford there simply was not as much existing infrastructure in place until recently. The Permian had a network of pipelines before the shale boom, and major infrastructure companies have offices in the region. In that race, the Permian was already around the first curve by the time other regions got out on the gate.

In addition to infrastructure, the Permian Basin has something else that the Eagle Ford can’t offer: Midland and Odessa. Oilfield companies need cities that can attract and support their workforce. Midland and Odessa have the economy, education system, and living standards that employees want, and major oil companies have been based in the Basin for a long time. “We’ve already had those guys [big companies] based here, and they built bigger offices to handle more,” said Edwards. “That’s the advantage over the Eagle Ford, the workforce. Small towns around the Eagle Ford were not prepared for that population growth and they’re really hurting right now.”

The Eagle Ford sits under a sparsely populated swath of South Texas. Before the shale revolution, Karnes County, which became the largest producing county in the Eagle Ford, had a population of just 14,865. As the Eagle Ford was heating up the small towns in the area struggled to support the burgeoning workforce and many settled in San Antonio, commuting 50 miles to the heart of the play. Then when oil prices plummeted, many producers in the region were forced to make substantial layoffs and when they did, those workers couldn’t remain in the small towns in the surrounding area. There simply wasn’t enough economic opportunity to hold them over until prices picked back up. These logistical challenges make it much easier to operate in the move-in ready Permian Basin.

Besides the infrastructure advantages, the Permian Basin stays longer and comes back quicker than the Eagle Ford for another important reason. “We’re seeing a faster recovery in the Permian because of higher crude oil content,” Bob Williams explained. “The Eagle Ford went down faster and harder than the Permian because natural gas liquids were a bigger part of the play there.”

Higher proportions of crude oil to natural gas liquids makes the Permian plays more lucrative than those in the Eagle Ford and, as a result, Permian unconventionals are disproportionately represented in the rig count recovery this year. Most of the action has been in the Wolfcamp and Wolfberry, even though drilling costs have been higher there than in many places in the Eagle Ford. The higher crude content makes all the difference.

Lease acquisitions by major oil companies reinforce this point. ExxonMobil already had more than 1.5 million acres in the Permian when its subsidiary XTO Energy snapped up 135,000 more acres in 2014. Pioneer also added to 28,000 acres to its significant Basin holdings in June 2016 through a sale with Devon.

There have been times when had Texas been its own country it would have been the sixth largest oil producer in the world, and going forward Texas can still expect to be the most productive oil state in the United States. While the days of LNG drilling in the Barnett look to be long gone, the continued prevalence of unconventional oil plays in the Eagle Ford and Permian Basin will carry the torch. The Permian may hold advantages over its younger brother, but together the two Texas plays look about as prepared to catch onto a price recovery as any other oil plays in the country.

Chase Beakley is a frequent contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine. He lives in Odessa.