Refracturing gives producers another crack at declining wells. Improved frac procedures and the opportunity for strong cost-benefit balances are behind the renewed interest in refracturing.

By Paul Wiseman

Much like the rise in horizontal drilling that started a few years ago, industry veterans realize that refracturing is not so much new as it is renewed. Stephen Trammel, Director of North American Well and Production Content for IHS Markit, an international think-tank that covers a variety of industries, says the first refrac happened shortly after the first frac in the early 1950s.

“By the early 1970s, refracs accounted for approximately one-third of the fracturing treatments,” he said, adding that these were basically all vertical wells. Few companies were drilling horizontally then. “Those wells benefitted from a much narrower pay zone and it just wasn’t that expensive.”

What exactly is refracturing: Definition

With the recent rise in refracturing the more complex horizontal and directional wells of late, defining exactly what that entails becomes important, for tracking reasons if nothing else. This involves two steps, the frac then the refrac. “Our [IHS Markit] definition of a refrac is where the company has completed a new well, they’ve drilled it horizontally or vertically or directionally, and they have stimulated the well with something,” most likely a hydraulic frac, in a staged fashion.

Refrac’ing, then, means that “Sometime later in time they will come in and refracture that same original zone.”

If, on the other hand, the producer re-enters with a drilling rig and cuts more footage, fracturing new zones as well as the previously drilled zones, Trammel says his company sees that as an overall recompletion with new perf zones.

What exactly is refracturing: Procedures

While refracturing is still in its infancy as done in directional and horizontal wells, there are a number of popular options now. Most are related to primary fracturing methods. One such procedure involves mechanical isolation with lines and plugs, using packers to isolate pay zones. One procedure primarily used in refracturing is called a diversion. This involves putting “agents and materials in to plug fractures or perforations to allow the frac to move to new areas,” said Trammel, noting that this method can be difficult to control.

Yet another option is the straddle frac, which uses packers to isolate the well bore. Each of these methods works better in certain types of wells than in others.

In truth, many operators admit that refracturing is so much in its infancy that they have a lot to learn about what procedures work best and which wells are candidates and what formations respond to it the best.

Why refrac?

There are two main forces driving the upward curve in refracturing. First would be its economic benefits as compared with drilling new wells, especially with oil prices stuck in the high $40-per-barrel range. Second is the great improvement in production from frac techniques today over what was in place 4-5 years ago. Producers say, in effect, “I wish we’d frac’ed then the way we do now.”

Cost-wise, Trammel used a recent Eagle Ford well as an example. A new well would cost $2.4 million to frac, whereas a small refrac would cost $1-1.5 million. It is possible to spend more on the refrac than on the original frac, but the use of modern procedures could generate enough additional production to pay the difference.

Those newer techniques come from greater understanding of formations in which the wells were originally drilled.

“The E&Ps have improved their techniques and, especially by using stages and clusters closer together in the wellbore, pumping up the proppant amount pumped per lateral foot to make sure they’re holding those fractures open” and other improvements, today’s fracs bring more production.

Which wells to refrac?

Selecting the proper candidate wells is what makes or breaks the deal. Number one would be, according to Trammel, “Target wells with known reasons for underperformance.”

Large gaps between original frac and current frac techniques would be one reason. More fracs today can catch producing zones missed the first time.

Field specifications also come into play. Is there one well in a field whose production is significantly less than others nearby, with no known geological reasons for the difference?

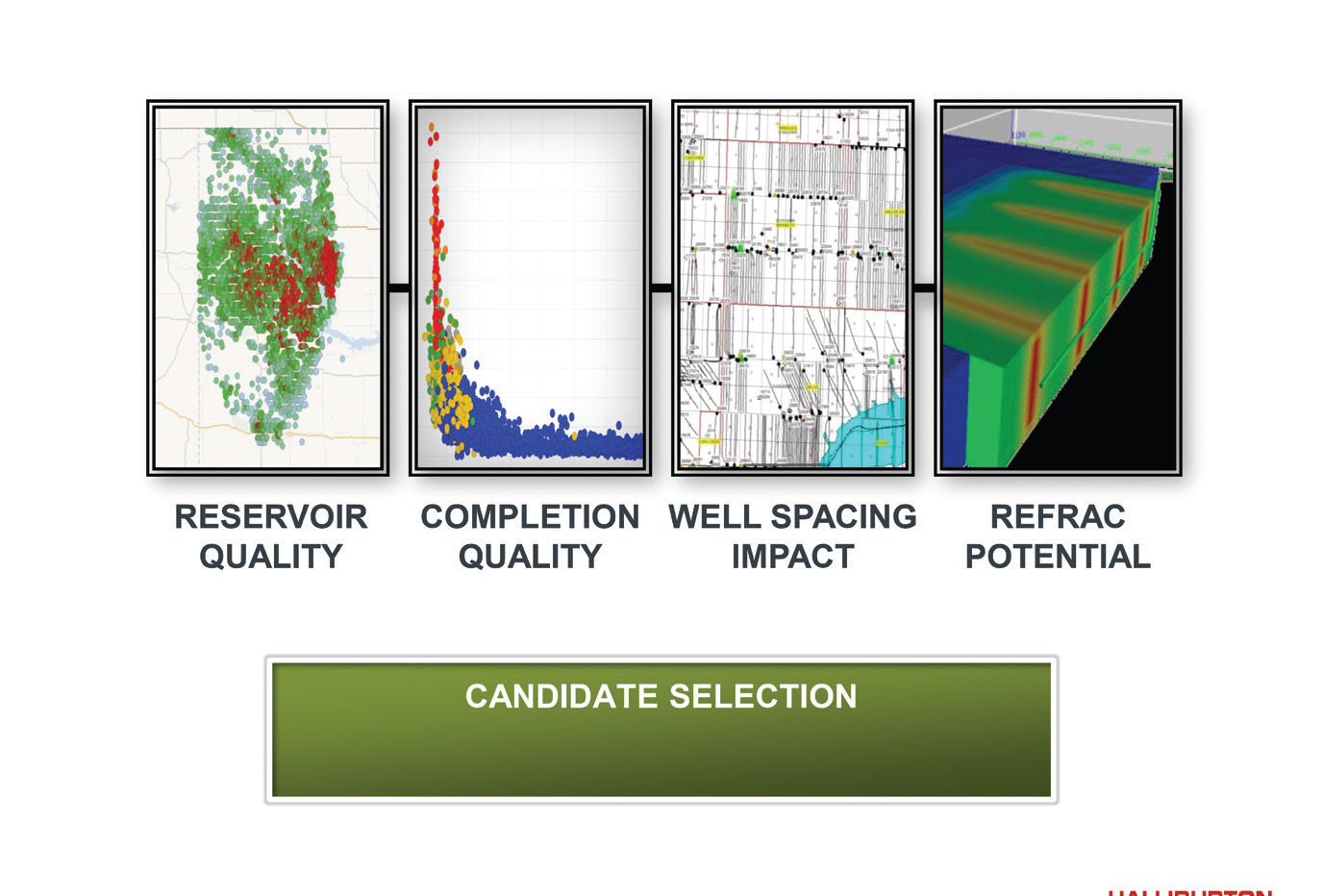

Jason Baihly, Commercial and Risk Assessment Manager, North America for Schlumberger, says there are certain things to look for in vetting a refrac candidate.

“We look for good reservoir quality, we look for sufficient pressure remaining because you have to have enough energy to clean up some of the frac fluid and drive the reserves out of the ground. We look at the lateral landing location to make sure the lateral is in the proper zone” where a refrac will help. “And we’ve got to have economical reserves in place that are recoverable.”

Over-pressured plays are higher on Baihly’s radar for refracturing than are plays below normal pressure.

Baihly says improvements in frac methods today compared to those of five years ago is not, by itself, reason to refrac, noting that if a well responded strongly to the first frac, a refrac may not be in order. It’s more important to decide what might be causing the lack of recovery in a certain well. “If there is an issue [such as] scale damage or heavy components in the crude flowing part way and restricting frac conductivity, I don’t think the size of the original frac really matters,” he said. If a well originally produced properly then begins to decline faster than its peers, a refrac may be in order.

He also sees refracturing as less of a decision between drilling and refracturing than a straightforward calculation of whether a well is a candidate for the process, with drilling new being a separate decision.

If there is overlap it may be an asset decision. A producer may have drilled all its best candidates in a field, so the best way to boost recovery is to refrac existing wells.

Who is benefitting the most from refracturing?

Taking all basins together, Trammel noted that less than one percent of all wells are being refractured, so the sample size is small. The percentage in the Permian Basin is even smaller.

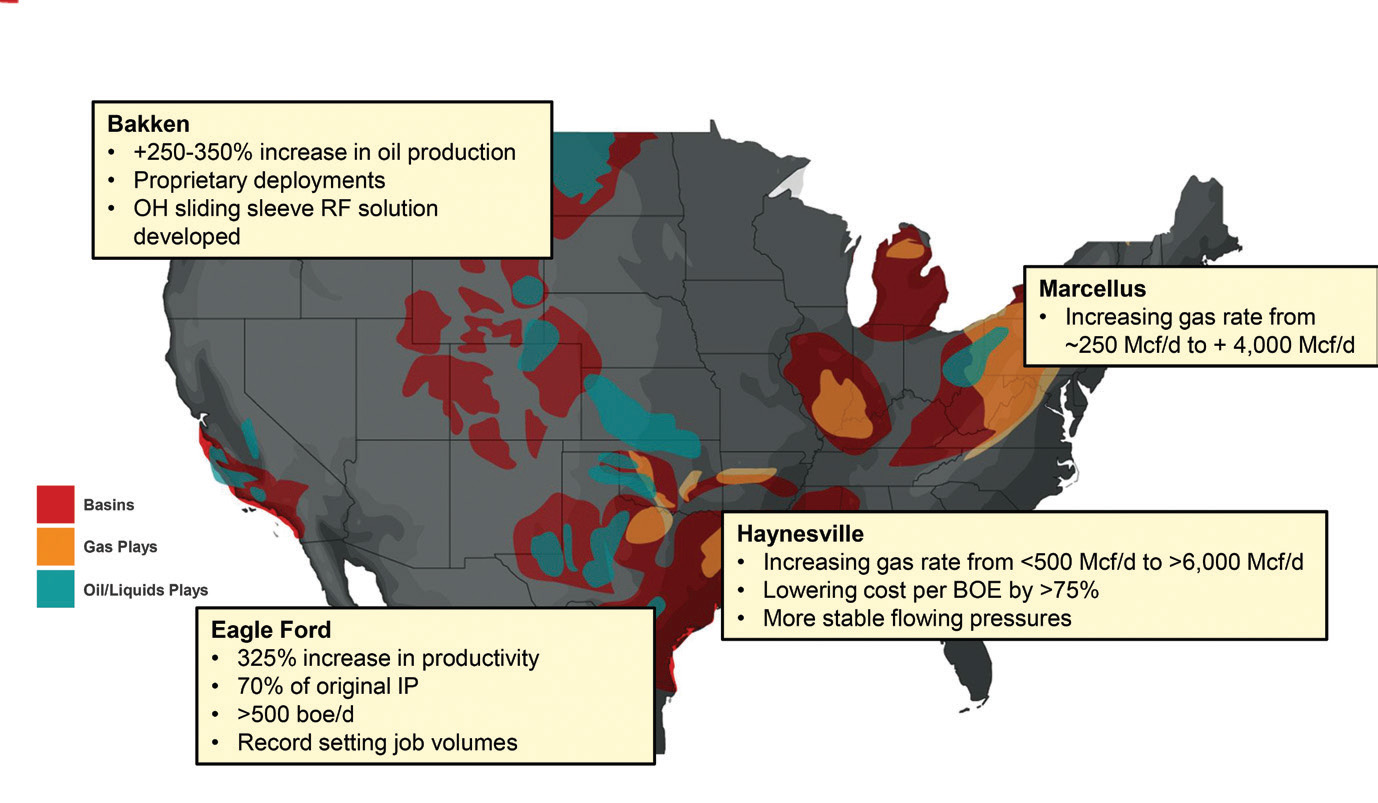

Where there is enough activity to track, some significant production gains are being seen. In the Bakken, refractured wells average an EUR (Estimated Ultimate Recover) uplift of 30 percent; in the Barnett’s Fort Worth Basin EUR uplift is 73 percent; Marcellus is 137 percent; and Eagle Ford’s number is 107 percent. All numbers are based on Halliburton statistics.

“When you see those kinds of EUR uplifts, I think for the Permian operators it’s going to be a no-brainer for them.” That will be in the future because, based on IHS Markit’s definition, there have been fewer than 100 horizontal wells refractured in the Basin in the last 2-3 years.

What’s happening in the Permian Basin?

One company that is seeing the number of Permian Basin refracs start to rise is Houston-based Mohawk Energy. The company’s Executive VP and cofounder, Scott Benzie, says they’re working with five or so operators in the Permian Basin. He agreed that there is much to learn.

“Refracturing, from Mohawk’s point of view, is embryonic technology, I would call it. Everyone has talked about it for the last 2-3 years but no one’s done a lot of it,” Benzie noted. Many operators don’t have the funds to do refracturing at $45 per barrel prices.

Mohawk’s niche is in “giving the operator a new wellbore to work in,” said Benzie. The advantage is in giving the operator a fresh wellbore, integrity-wise, while the challenge is that it’s with a slightly smaller inside diameter because there is a patch in the well. He noted that this ID is still larger than a coiled-tubing deployment, which is another option.

He noted that recompletion methods done in the Barnett, Haynesville, and Eagle Ford, where operators simply pump more frac fluids into the hole, or the “bullhead technique,” as he termed it, are successful there but would not apply to Permian wells. “What they’ve seen to date, as they pump fluid and proppant down, is that treatment is limited to the heel 1/3-1/2 of the lateral, proppants and fluids don’t get beyond half lateral or the towards the bottom of the well.” This lack of control leads to an unevenly distributed treatment resulting in over capitalizing.

Because there have been so few refracs, Mohawk has mainly used its relining technology on new wells where the frac failed and needed, basically, a do-over.

Who wants to go first? Not I!

In this economy well operators are nervous about the costs and opportunity for failure with refracturing, especially the well engineers who may be concerned for their jobs. So “They have a well that’s producing now, albeit at a low rate, they don’t want to take that well offline, go in and set one of these long liners, a lot of money, and then restimulate hoping to get a higher production quantity,” he said. In effect, everyone wants someone else to do it first, a common malady suffered by new technology. Early adopters are often few and far between.

The company has one upcoming restimulating project in which the producer can see they are not getting production in all zones. “So they’re going to get huge uplift in terms of more lengths of the horizontal producing,” he said. “Then they’ll be using newer proppants and newer techniques on how to pump that frac.”

Benzie’s cost figures for the Permian Basin indicated a new horizontal well would cost around $5-10 million while refracturing involving Mohawk’s liners and the other stimulation costs would total about $2 million. This would make refracturing a much less costly procedure.

All agreed that much is yet to be learned about everything from how to select good candidates to the right ways to proceed. Jason Baihly noted that a method that works well in one basin may not work at all in another.

And today’s percentage rate of success or failure will weigh heavily in deciding the future of refracturing. If further refinement leads to a success rate in the range of 75 percent, Baihly feels refracturing will gain significant traction, referring to it as an additional secondary recovery method. If the rate never passes 50 percent, producers will look elsewhere for the most part.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer living in Midland.