As usual, the oil industry has seemed to turn on a dime. Two years ago producers were filling swimming pools with excess oil because it was a commodity nobody wanted during the Pandemic. In 2022, it’s still a commodity that certain groups don’t want, but they have to admit they need it. That’s due to worldwide crises combined with hard facts about the energy transition—it can’t happen today, tomorrow, or possibly ever, at least not in the scale required to energize the entire world.

While the world reels from the loss of one of its top oil and gas suppliers, suddenly those U.S. producers are being begged to “drill baby, drill” as opposed to “keep it in the ground.” But neither the upstream (drilling) nor the midstream (pipelines to refineries and markets) are able to simply flip a switch.

Production takes months to get online and pipelines take years of open seasons, design, right of way procurement, and construction—not to mention tens of millions of dollars—to put into service. Plus, pipelines face much more resistance from environmental and regulatory agencies, causing some to be canceled or greatly delayed after the expenditure of millions of dollars. And while Texas is generally more friendly to the oil and gas industry, even this area has seen some resistance.

Suzie Boyd, founder and president of midstream consultant firm Caballo Loco, says the investment climate is suffering from both the ESG challenges and pricing uncertainties. “While Texas is generally a pipeline friendly state, there are more and more obstacles to new construction,” she said. “This comes in the form of environmental activists as well as folks who just want to put up barriers against any type of hydrocarbon expansion.” Investor ESG pressure is also a factor.

Midstream is Not Without Complexities

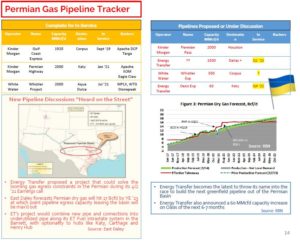

She noted challenges to the path of Kinder Morgan’s Permian Highway pipeline near Austin in 2020. Even though the line was approved, reaching full commercial service in January of 2021, it faced more challenges than Texas midstream companies are used to. Permian Highway delivers natural gas from the Waha hub to the Gulf Coast and Mexico markets.

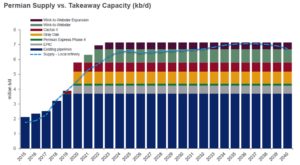

In the oil-rich Permian there are plenty of oil pipelines, Boyd noted. The problems arise in takeaways for what is a byproduct here, natural gas. In the years leading up to 2020, a shortage of natural gas takeaway capacity created two main problems: negative prices at the Waha hub, long before oil suffered the same fate in April of 2020; and a massive flaring issue. Some experts estimated that enough gas was being flared each day to generate electricity for the entire state for one day.

Some of that backlog began to be solved by new lines, including the aforementioned Permian Highway. Boyd noted, “The industry experienced the lack of gas pipeline capacity back in 2019. We saw flaring at that time, some related to price and some related to lack of midstream and processing infrastructure. At the moment, there is adequate midstream infrastructure online or under construction. So the decision to flare would be largely based on price.

“What we saw during 2019 was the concept of a negative price for gas. This allowed Permian producers to keep producing while gas in other, less profitable basins was shut in. Remember, Permian gas also comes with an associated natural gas liquids component as well as crude oil, which allows it to remain profitable even when the residue gas is negatively priced.”

Gas Pipeline Capacity Today and Tomorrow

With the U.S. Energy Information Administration reporting all-time record oil production for the Permian every month so far since December 2021, many wonder how the midstream capacity will hold up. Boyd notes that, although the Permian Highway was joined by the Whistler pipeline as 2021 additions to gas takeaway, that excess capacity is proving short lived. While there is technically enough outbound capacity, to keep Waha prices up, some of the pipelines go to less desirable markets, which means there won’t be enough buyers at the other end to justify capacity use.

Beyond the years when producers had to pay at the Waha hub for takeaway capacity, there is always a difference between the Waha price and the Henry Hub price, Boyd said. That is known in the industry as the “Waha basis.” The Henry Hub is located in Erath, Louisiana, just south of Lafayette.

Plus, as of this writing there has been an issue with Kinder Morgan’s El Paso pipeline, removing a significant amount of capacity from the market. Problems relating to an August explosion along the line in Arizona are yet to be resolved.

Boyd reports that no new gas lines are in the plans, except a modest expansion to an existing line planned for later in 2022.This could be a problem because “the industry is projected to need another 2 Bcf per day (at least one pipeline) by mid to late next year. Since it takes up to 2 years to construct, the industry is waiting to see if any company will step up,” Boyd said.

Energy Transfer and Kinder Morgan have both expressed interest, but they need producers to commit to pay in the form of a fixed tariff for up to 10 years. That means they will guarantee to either upload gas or compensate the company monetarily if they don’t. Boyd says, “That’s a tough commitment to get from producers that are dealing with investor pressures.” On the other hand, for producers to insure their will be a home for their gas to avoid playing, those commitments are required.

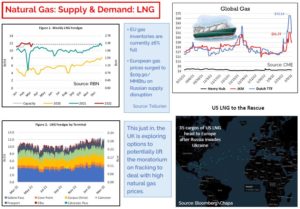

The gas pipeline shortage issue is much more pronounced and chronic in the Northeast, which is famous for importing LNG from other countries while nixing pipelines from Pennsylvania left and right. To the question as to why they can’t just import more cleanly produced LNG from plants in Louisiana or closer, Boyd refers to the Jones Act. It requires goods shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on ships that are built, owned, and operated by United States citizens or permanent residents. Boyd points out that there aren’t any LNG transport ships in that category—all are owned by foreign powers. That leaves the northeast with no U.S. sourced options.

According to the March 2022 Caballo Loco newsletter, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has recently released new guidelines for pipeline approvals, which may further challenge new development.

FERC will now evaluate new projects across four categories.

- Developer and customer interests

- Interests of nearby pipelines and customers

- Environmental impact

- Interests of landowners, environmental justice, and surrounding communities

The idea of the new guidance is to improve the legal durability of FERC’s natural gas certificate. Industry leaders expect the new policies to slow progress of new projects and to lengthen the time required for approvals.

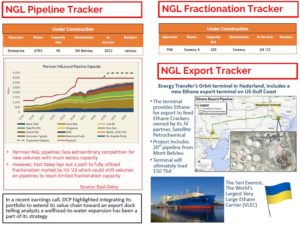

The newsletter, quoting information from S&P Global Platts, supports Boyd’s belief that the basin’s growing oil output could be hampered by gas takeaway issues, including the buildout of processing plants. It points out that, after years of building out long-haul oil pipelines, natural gas infrastructure is now in frantic catchup mode. Restrictions on gas flaring are growing, forcing more gas through processing plants and into pipelines, instead of into burners.

A capex slowdown by basin midstream companies over the last two years has created localized processing constraints. Should new gas infrastructure development continue to lag, there could be a return to discounts at Waha and, eventually, the actual shut-in of oil wells due to stranded gas.

A Glut of Oil Pipelines

Due to a massive buildout from 2016-2020 along with the production collapse of 2020, oil pipelines are currently overbuilt in the region. But with the EIA’s previously mentioned expectations of further production growth, that could change in the next two-three years—which is a long time in pipeline life. Some have suggested a midstream company could convert an oil carrier to gas with reasonable effort, but no such projects have yet been announced.

Pipeline planning—always a game of “what if” and “maybe”—has become even more challenging as pandemics and global conflicts throw even more variables and sudden changes into the mix. And with opposition from sources ranging from ESG-concerned investors to axe-and-torch-wielding protestors (in February at a pipeline construction site in British Columbia), the challenges mount. Then there are employee shortages and supply chain difficulties for everything from steel to small parts.

Bringing energy to the nation is getting harder, even as it is more and more needed. These are not days for the faint of heart.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in oil and gas. His email address is fittoprint414@gmail.com.