“Go to the ant,” suggested King Solomon, because even without a company man, the ant “stores its provisions in summer and gathers its food at harvest.” Retired veteran oilman Mike Shellman admits that he is a contrarian when it comes to how fast and hard to push production from new wells. And he avoids shale production like the plague.

His main concern about the current climate of fast companies—drilling at breakneck speed, crowding wells at 330-foot intervals, and producing them like a firehose in a forest fire—is that this is shortsighted. It depletes reservoir pressure to the point of trickling out through beam pumps after a few years, effectively leaving the vast majority of a formation’s resources unrecoverable.

Forever, in his view.

The Drive Behind Being Driven

Why the frantic pace of drilling and production? In answer, Shellman sees dollar signs. “It’s all about money.” This is ironic because, “The tight oil business model is not very sound anyway. To me, it does not work economically unless people are constantly throwing money at it.”

He lists as an example Shale’s Roaring Teens—2014-2019 to be precise—when shale plays in the Wolfcamp, Bone Springs, and Spraberry were the Place to Drill. “When [shale producers] hit the street they were able to borrow billions and billions of dollars at practically no interest,” signaling the start of what he called the “growth-before-profit” model.

Therein private equity and other investors invested ain or outright purchased shale players with the express intent of growing the company many fold, then selling it for an exponential profit. The shale drillers “were able to use other people’s money. So instead of worrying about making a profit they were just trying to grow—growing reserves and production.” For the drillers themselves, the theory was “that they could have so much production that they could pay all that back.”

Unfortunately, says Shellman, as their production grew overall, many of those producers failed to admit that individual wells were declining precipitously.

By around 2017-18 prices had dropped, partly due to the worldwide glut of oil produced by the shale rush, and the grow-and-sell model was proven to be faulty. Suddenly, many of those investors found themselves actually having to own and operate those companies—at least those were the lucky ones. Those less lucky were faced with bankruptcy fire sales of their formerly golden geese.

Even now, Shellman says, as many of the majors are reducing their planned growth to single digits, the wells many of them do drill are pumped hard from the second the pump starts. This kind of push is what destroys pressures and strands assets.

The investor model has changed beyond the “growth-before-profit” model to simply making a profit, “so all of a sudden they’ve got to make a profit and return some of that profit to the people who loaned them all this money, and to shareholders. To me, that’s put additional pressure on them to optimize cash flow.” It still involves drilling a lot of wells and producing them quickly, but not quite as fast as they used to.

We’ve Got Black Gold Fiverr

For some, Shellman says, shale appeared to be without risk of failure. “You can lease almost the entirety of Midland County and you don’t have to worry about drilling a dry hole,” he said. The nature of shale, its abundance, caused some to throw caution to the wind. “We can drill these wells five at a time on a pad and then we can move over and drill five more. We can keep going and we don’t care about reservoir management. By the time these poop out we can go and drill another five.” It’s sort of a shale patch version of Fiverr.

The “no dry holes” mantra is especially true when drilling in the sweet spots. In an extreme version of the 80-20 rule, Shellman notes that “about 93 percent of all Permian Basin tight oil production comes from just some core areas in eight counties,” which amount to 13 percent of the 61 that are considered part of the Permian.

So What’s the Problem?

Shellman points out that, “The more overdrilled these core areas get, the faster the pressure depletes, and the less oil and condensate these wells make.”

Can’t they be beam-pumped after that? Well, he notes, “Artificial lift doesn’t stop the depletion process.” While those wells will produce for years that way, “They’re declining, and the rate of decline is accelerating.”

Some of that was news to the original shale producers because, “Twenty years ago some thought this was going to be a big, beautiful hyperbolic decline where these wells would settle in to making 50 barrels a day for a long time. Their decline curve had big, fat tails that would extend out 25 years, and the world would be full of shale oil.

“That ain’t happening, bro.”

Instead they make about 70 percent of their oil in five years, and the next 30 percent take another five, for a total life of 10-12 years. That 100 percent total of a well’s productive life only accounts for about 5-10 percent of the oil in place, stranding millions of barrels, possibly forever. Fracturing is part of the problem, he believes.

Hydraulic fracturing helps up front, but Shellman sees it as a further problem for long term production. “Think about the process of frac’ing: You’re hydraulically breaking up those minute little fractures in that shale and filling them full of sand. But when the liquid and the gas deplete out of those fractures, you get fracture closure. That’s a well-accepted fact in the business of frac’ing, whether it’s shale or anywhere, that those fractures don’t stay propped open for long—or forever,” he said.

And unlike conventional wells, Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) with waterflooding does not work in shale, because there is no communication between wells. So when the reservoir pressure is gone and the fracs have closed up, he sees little hope of reinstating the recovery.

Running (a Business) Against the Wind

“I, as a producer over the past 50 years, have the exact opposite business plan,” Shellman declared. “I’m in it for the long haul, and I manage all my reservoirs like they were my little children. I babied them along. Many of my wells have lasted 60-70 years before depleting.” Now retired, Shellman has passed those still-operating wells on to others.

Other Voices Chime In

Shellman’s views fit in with a few other contrarians including longtime industry consultant and blogger Art Berman.

In a January blog post entitled, “The Beginning of the End for the Permian,” Berman opens by saying, “Permian Basin and Eagle Ford oil recoveries have both fallen by 30 percent and Bakken has declined by almost 20 percent. Those plays accounted for two-thirds of U.S. output in 2023. That means that U.S. production will decline at some time in the relatively near future.”

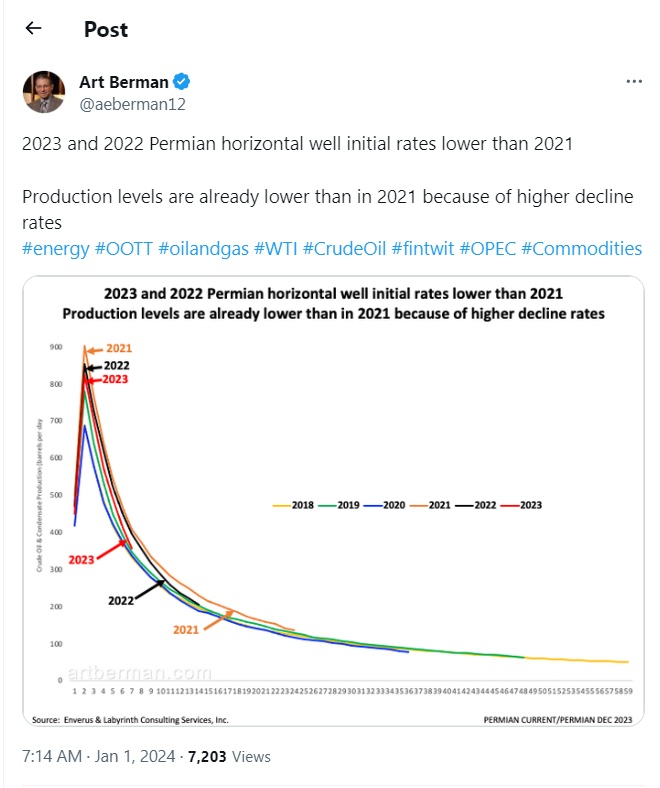

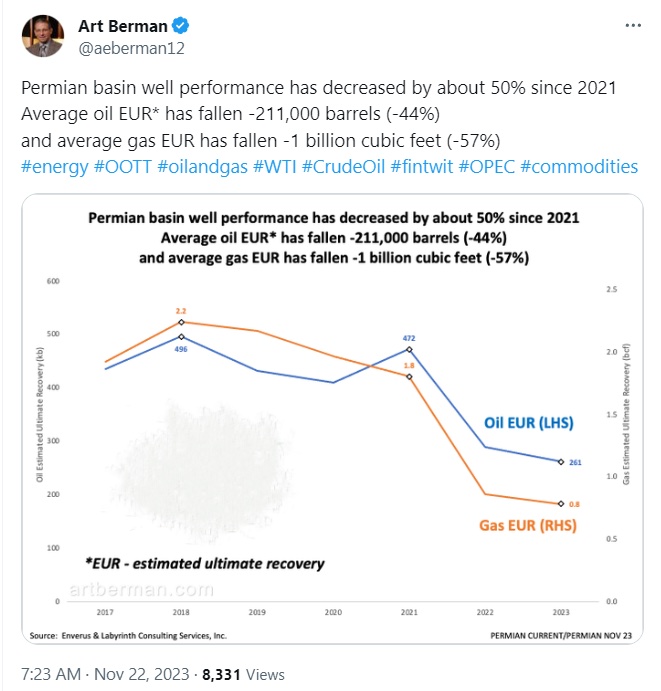

From a statement that seems to support Shellman’s contention of front-end overproduction, Berman says, “…shale wells are producing at higher initial rates but are declining faster than in previous years. Their total recoveries are lower than just a few years ago.”

In that blog he posts a graph [see accompanying graphic] from Enverus & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc. showing that Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) rates in an average Permian horizontal well declined 29 percent from 2021-2022 and 38 percent from 2021 to 2023.

Berman sees trouble for natural gas as well. In another January post, “Draining America First—The Beginning of the End for Shale Gas,” he points out that per-well production for natural gas is also dropping year-over-year, in almost every field including the majors like Marcellus and Utica—and once world-class fields like the Barnett and Fayetteville are no longer even up for discussion.

But it’s the future that concerns him. “I am frankly less concerned about whether or not shale gas production is currently in decline as I am about what will happen to supply in five or ten years…. Plans to increase exports by 15 bcf/d will put serious pressure on future supply regardless of whether or not production has started to decline.”

Low natural gas prices have prevailed since around 2018, Berman notes, greatly reducing investors’ long positions in the fuel because no one sees anything but a glut for the near future—unless exports significantly drain the supply.

Both men admit that they are pushing against the conventional wisdom, and they seem genuinely concerned that the prevailing view will have serious consequences for the industry and for consumers sooner rather than later.

Related: The Future of EOR is Now