In many ways, the story of drilling is the story of the drill bit. As that device has changed, so has the entire enterprise of making hole.

by Bobby Weaver

In today’s world the speed and efficiency of drilling oil wells has reached a level undreamed of by early day oilmen. The evolution of the drill bit over time is largely responsible for that progress. Recently a world’s record of 5,146 feet—scarcely short of a mile—was drilled in a single day and 9,862 feet was also drilled in one 48-hour time frame. Those fantastic accomplishments aside, today’s oilfield average well drilling time in the Bakken of North Dakota is routinely recorded as 15 to 30 days for wells drilled 10,000 feet vertically and 10,000 feet horizontally. This remarkable accomplishment is the end result of a long and painstaking evolutionary process.

It all began in 1894 when rotary oil well drilling was first introduced at Corsicana, Texas. Those wells were drilled vertically and indeed all oil wells were destined to be confined to that process for the next 90 years or so. The drilling speed in those first days was only a few feet per day. Early on the new fangled rotary method was confined to the soft unconsolidated formations of the Gulf Coast, where traditional cable tool methods had proved unsuccessful.

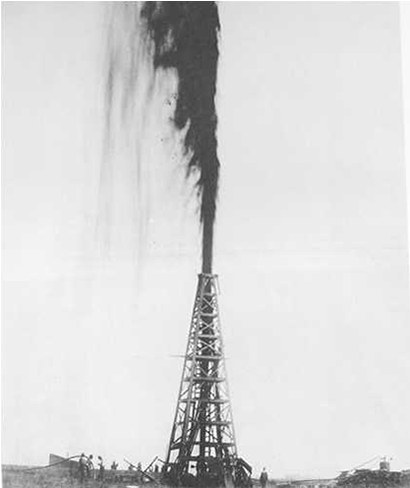

The first major well drilled by the new method was the Lucas Spindletop discovery well completed near Beaumont, Texas, on January 10, 1901. That well was drilled to a depth of 1,020 feet or maybe it was 1,160 feet (there seems to be some controversy concerning the exact depth due to the scanty records of the era) over a period of 45 days for an average of 20 to 25 feet per day. It was not the fastest well ever drilled, but it was perhaps the most important, because its massive production inaugurated the beginning of the modern petroleum industry.

The bits used on the Lucas well were of the drag or fishtail variety. The drag bit was simply a chisel shaped device that scraped its way downward through the earth. Its variation was the fishtail bit that was made by splitting the drag with one half of the cutting edge facing forward and the other half facing backward similar in shape to a fish’s tail. That type of bit was destined to remain the primary rotary bit used up until the mid 1930s. It worked very well in the softer formations on the coast, but it performed poorly in harder formations further inland. In reality it was little better that the old fashioned cable tools used to drill most of these shallow (less than 4,000 feet) wells of the day.

As the Gulf Coast oilmen developed a familiarity with local drilling problems, they introduced modifications to the drag bits that generally increased drilling efficiency. Those early bits were made of 30 percent carbon steel that could be forged and sharpened many times over without damaging the hardness of the metal. Consequently, hundreds of little blacksmith shops specializing in sharpening bits sprang up at every new discovery. Each drilling rig dulled as many as two to six bits per day, for which the blacksmiths charged 25 cents per diameter inch to dress them. Additionally, it seemed as though every driller had his own particular type of design that he liked to use. To say that there was any sort of standardization would be a total overstatement. Consequently all those little blacksmith shops were littered with piles of bits of varying designs and shapes, with each pile earmarked for some particular driller.

With the advent of electric arc welding, beginning in the early 1930s, hard facing of drag bits became possible. That rebuilding of the bit face with harder metals before sharpening greatly increased their drilling efficiency from a mere 50 to 75 feet per day to as much as 150 to 200 feet per day. Shortly thereafter, the use of tungsten carbide inserts as cutting edges increased the speed up to a rate of 400 to 450 feet per day. Thus, the drilling speed gradually increased, although the drag bits still performed poorly in harder formations, such as those encountered in the Permian Basin when it began to be drilled in the mid 1920s and early 1930s.

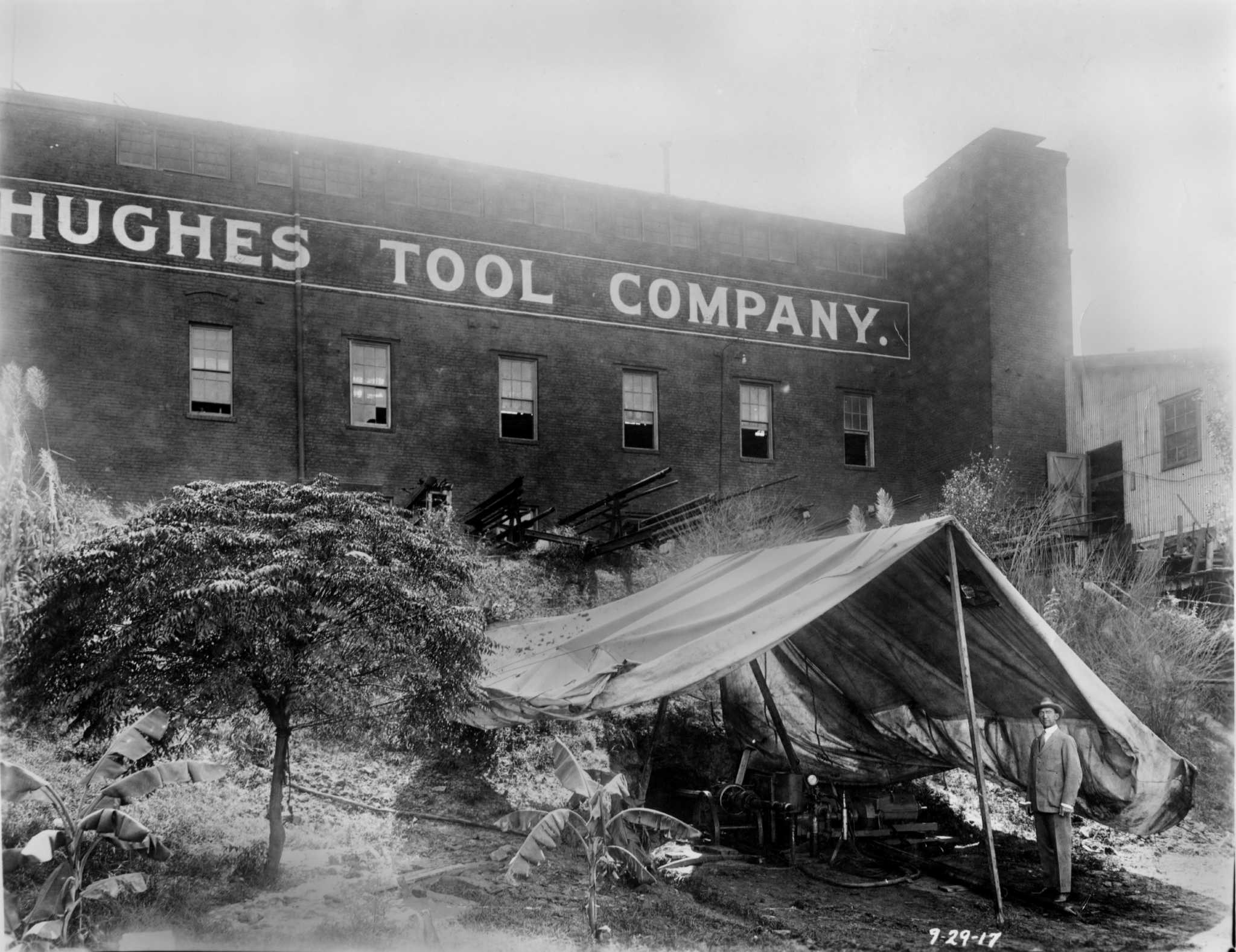

07/1917 – The horizontal boring machine setting inside the tent was invented by Howard Hughes Sr. to bore underneath enemy trenches in World War I, but was never used. The original device is housed in the Drilling Simulator Lab at the Hughes Christensen facility in the Woodlands. courtesy: HPL-Houston Metropolitan Research Center, RG1005-1932

While all this improvement in the cutting ability of the drag bits was going on there was another ongoing problem of standardization to be solved. When those first rotary wells were drilled they used an eight-thread-per-inch system on the drill pipe and bit shanks. Much like the individual variation on bit design, personal preferences on thread size soon arose. It did not take long before there were as many as 26 variations of types and sizes of threads for bits and drill collars being used. It doesn’t take too much imagination to understand the nuisance value of such an uncontrolled system. It was not until 1923 that a resolution submitted to the API Standardization Committee created a standard tool joint thread size arrangement that made all those drilling components interchangeable.

Meanwhile, location of the drilling fluid jets was coming under closer scrutiny. It was fairly well understood through practical experience and observation that the drag bits used in the softer formations worked better if the fluid jets were as close to the cutting edge of the bit as possible. Consequently there were a host of improvements made during the first 20 years of the industry in that regard.

Until approximately 1930, little interest was given to keeping well bores straight. That was about the time that wells in the 8,000-foot range began to be drilled, especially in West Texas. It was generally agreed that drag bits created greater problems toward drilling straight holes than rock bits (ie. roller cone bits) did, and a great deal of experimentation concerning weight, variation in use of drill collars, pipe revolution speed, and mud pressure was made to improve the situation. All that experimentation combined to bring the blade-type drag bits to their highest level of efficiency, but by that time they were being eclipsed by the roller cone bits.

The Lucas Spindletop gusher—a well that made history in more than one way. Besides its profound oil strike, the well was notable for its breakthroughs in drilling mud and in drill bits.

What has been described by many as the greatest oilfield invention of the 20th century, the roller cone bit, first saw the light of day in 1908. It began as the brainchild of John S. Wynn, who operated one of those little blacksmith/machine shop/supply house operations following the Gulf Coast booms. One day as he sat in his shop at Sour Lake he began idly playing with a device known as a pipe setter. As he spun the object he noticed that it rotated on its roller cones in a perfect eight-inch circle. That observation gave him the idea of developing a bit utilizing two opposing roller cones that would chip away at the surface of the rock instead of scraping it off.

Wynn invented and patented the device in 1908, but it met with little success. Shortly afterward he moved his shop to the Batson boom and took his device with him. It was there that a drilling foreman for the Sun Oil Company who was having a problem drilling through a particularly hard formation decided as a last resort to try the roller cone bit. After the bit was attached and drilling began, the driller thought that the drill pipe had twisted off due to the ease of rotation. After drilling 65 feet, the bit began to drag and upon coming out of the hole they discovered that one of the cones had chipped, causing that cone to lock up. Wynn repaired the device and they finally drilled through 134 feet of rock in record time.

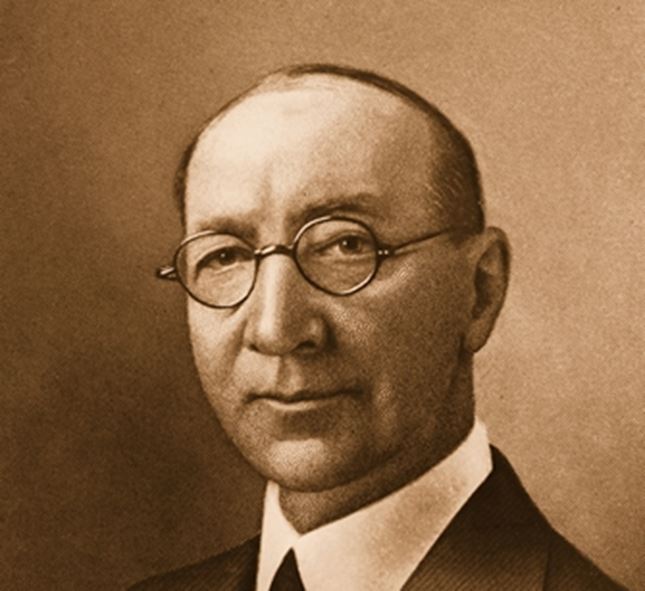

Legendary Houston oilman Walter Sharp heard of the incident and sent a business associate named Howard Hughes Sr. to investigate. Hughes borrowed the bit, took it to Houston for inspection and trials, and was impressed with its potential. He and Sharp formed the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in 1909 and immediately bought Wynn’s patent for $6,000. They also bought patents on several other similar devices and, using the Wynn prototype as a model, Hughes began refining the bit into a highly efficient drilling tool. They considered the invention so important that all experiments were carried on with the utmost secrecy. When it was tried out the bits were carried to the rig in a burlap bag and the entire crew was escorted off the drilling floor until the bit was attached and lowered into the hole. When the experiment was completed the crew was once again removed until the bit was again out of sight in a bag. By 1910 the device was perfected to Hughes’ satisfaction and it rapidly became accepted as the ultimate rock-drilling tool on rotary rigs. Upon the death of Sharp in 1912 Howard Hughes assumed ownership of the corporation and three years later it became the Hughes Tool Company. At the time of his death in 1924 Hughes held seventy-three patents, all associated with his original invention in one way or another.

The Hughes Tool Company had an active research and development program that continued to produce improvements in their product, which they provided strictly on a lease basis. Then in 1933 they patented the tri-cone drilling bit and abandoned the original two-cone product. Initial trials of the new bit produced a 50 percent faster drilling time and greatly enhanced the ability to maintain a straight hole. From then until 1951, when the patent ran out the tri-cone bit, the Hughes company was able to maintain an almost 100 percent control of the drill bit business in the oilfield. During all that time they maintained their strict lease policy.

The next major change in bit technology occurred in the 1970s when downhole drilling motors (i.e., mud motors) allowed more rapid spinning of the cutting edges of the bits and greatly increased drilling speed. Mud motors combined with enhanced technology controlling precise directional drilling eventually led to the ability to drill horizontally. In 1981, George P. Mitchell began experiments in the tight gas formation of the Barnett shale in Wise County north of Fort Worth. From then until 1997 Mitchell spent an estimated $250 million and untold hours perfecting the technique of using horizontal drilling combined with hydraulic fracturing to release the massive amount of gas and oil in the Barnett. Since then the technique has been significantly refined by a number of operators and has in effect rejuvenated the oil and gas industry in the United States.

Thus from the beginnings of rotary drilling, when drag bits made only a few feet per day on vertical wells, to the present, when drilling is measured in terms of thousands of feet per day in any controlled direction from vertical to horizontal, advancing bit technology has led the way. The industry has always kept turning to the right and there is no reason to think it will not do so in the future.

Bobby Weaver is a frequent contributor to PB Oil and Gas Magazine. His humor column, “Oil Patch Tales,” resumes in this issue after a brief hiatus.