This approaching flood will require water treatment instead of an ark.

by Paul Wiseman

Grizzled veterans of the Oil Patch have a saying that goes something like this: “We produce mostly water and a little bit of oil.”

In the days of vertical w ells and falling production that issue was not a problem. Scattered disposal wells could handle the flow and the practice of recycling water was unheard of because fresh water was cheap and plentiful.

ells and falling production that issue was not a problem. Scattered disposal wells could handle the flow and the practice of recycling water was unheard of because fresh water was cheap and plentiful.

The advent of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, featuring miles-long laterals and the need for tons of proppant and millions of gallons of water, has changed that landscape drastically already—and that change could reach crisis proportions in the next few years.

Warren Sumner, president of Orion Water Treatment, says, “The number one trend I see is that the volumes of treated water are going up substantially.” Increased efficiency on the part of producers has made $60 oil profitable, so drilling activity has increased—creating more and more produced water.

So much so that, said Sumner, the volumes are starting to strain the capacity of existing disposal wells. This, and the fact that fresh water required for fracturing is beginning to get scarcer and more expensive, creates the need for producers to look more seriously at treating produced water for reuse in frac’ing.

Producers are being driven to treatment and reuse of produced water also because treatment costs have dropped to the point that it is no longer just the “right” thing to do, it’s actually cheaper. This is especially true when factoring in costs saved by avoiding injection expenses.

These fiscal facts have encouraged a growing number of companies to jump into the treatment business. Sumner feels that the plethora of treatment options and the fact that there are still other options keeps the price of treatment down.

“In the oilfield, everybody wants the next innovation; and they want it cheaper,” said Sumner. “You don’t get a paradigm shift without a price decrease,” he added, explaining the increase of companies moving from disposal to treatment.

“Today, producers are still able to satisfy most of their frac’ing requirements with local sources of water, without reusing produced water,” he said, referring to fresh and brackish groundwater.

That and the influx of water treatment companies have made the market “brutally competitive. Every deal we’re in has at least five or six bidders, and we’re all at about the same price. We’re at the lowest possible price we can do it for.”

Sumner sees hope in the fact that some experts believe the Basin will produce up to 10 million barrels of water per day within the next 2-3 years, changing the supply-demand dynamic more in favor of the suppliers.

To put this number in perspective, the entire U.S. oil industry averaged 10.2 million barrels per day in January of this year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (eia.gov/outlooks/steo/report/us_oil.php).

If oil prices stay at around $60 per barrel for the next two years or so and frac volumes continue to grow at their current rate in the Permian Basin, “then producers are telling us [that] within a couple of years their produced water volumes are going to be so large that they will have to find alternative uses for it,” Sumner said. That, combined with a lack of available ground water for the immense frac’ing requirement of so many wells, may force even more producers to treat and recycle produced water.

That situation might create more demand for treatment than supply, allowing treatment firms to move away from rock-bottom pricing.

For Sumner, this connects to the concept of “highest and best use” of water. “Ideally, fresh water should never be used in industrial applications,” he said. Instead it should be reserved for municipalities, farms, and others. Produced water can’t be used by those entities, so it’s appropriate for reuse by the industry that generated the supply, in Sumner’s philosophy.

Innovation Required

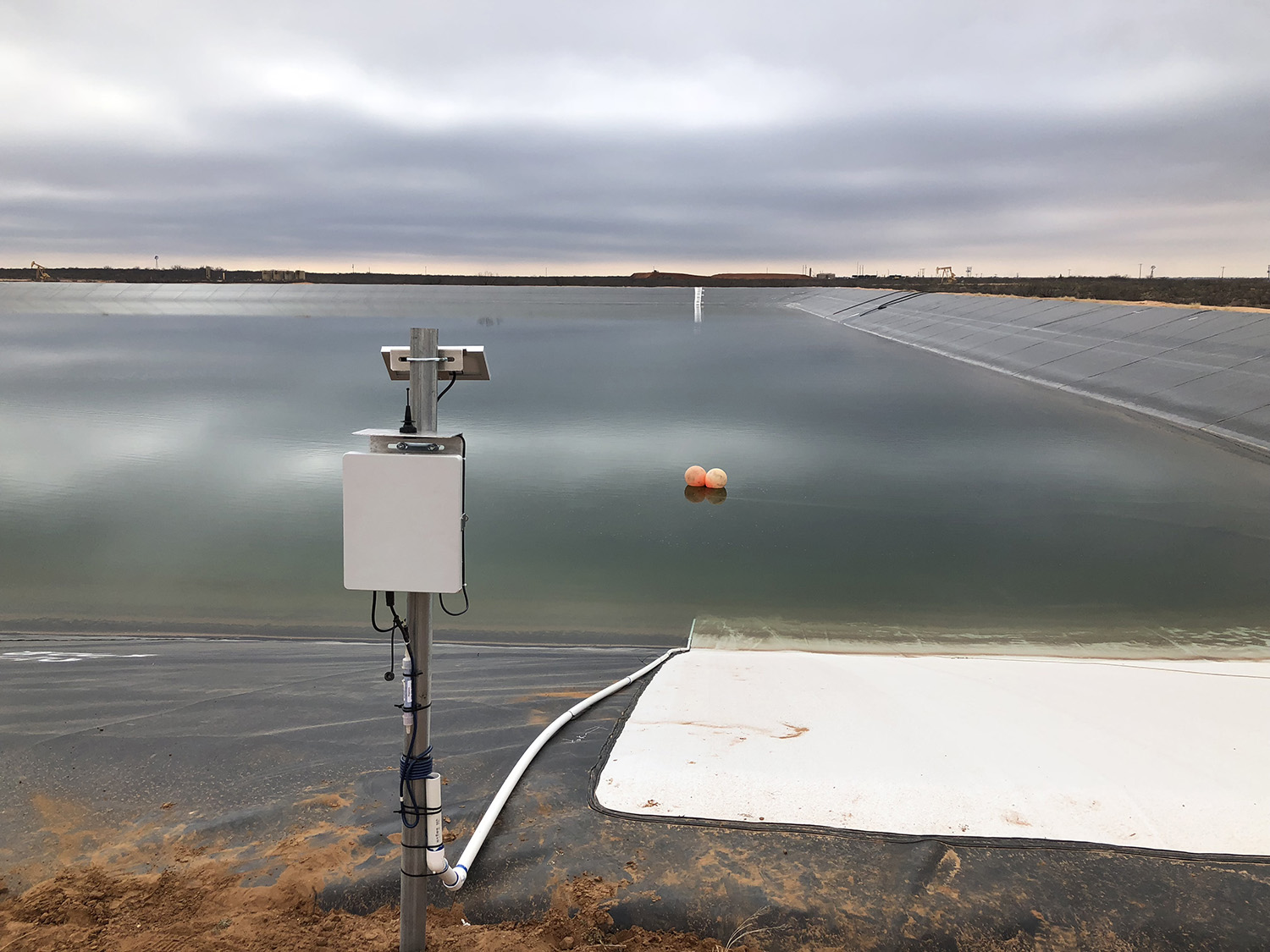

The need for producers to keep track of the millions of gallons of treated water stored in lake-sized frac pits gave Randy Smith an idea for a business. Already in the water transfer business, Smith, president of TransWater, Inc., says he encountered several clients who did not know how much water they had in those pits.

The need for producers to keep track of the millions of gallons of treated water stored in lake-sized frac pits gave Randy Smith an idea for a business. Already in the water transfer business, Smith, president of TransWater, Inc., says he encountered several clients who did not know how much water they had in those pits.

Smith wondered if a sonar unit could be mounted on a remote-controlled boat to measure water depths and to detect changes in the contour of the tank bottom. If those numbers could be processed in a way that would give the producer an accurate accounting of the pond’s contents, it would be a very valuable number.

“I started doing research and I found a remote-controlled boat, a product that would actually—safely—go in the frac pit, whether it be fresh or produced (water) and, with sonar, measure what they call bathymetry, which is everything under the surface of the water,” Smith said. The existing boat’s system would tell the operator how much water was currently in the pond. Smith extended the reporting to list the pond’s potential capacity were it to be filled to the highest acceptable level.

These boats were already in use in Europe measuring boats and rivers, with some applications in the mining industry.

TransWater’s Director of Business Development, Steve Pruitt, adds that the boat originally just gave a snapshot of a moment in time. “The next generation of the company came to be when people said, ‘That’s great, but what if I’m in the middle of a frac and I’m not sure how much I’ve used?’” They wanted to know if they had too little or too much—and use this data to help them allocate water for future frac jobs.

The company then partnered with another company to develop a way to monitor water use as well, giving producers the information they needed.

Like Sumner, Smith sees a growing expense for producers who simply want to dispose of produced water—making the monitoring of frac pits essential.

“A lot of companies—and it used to be just the larger operators [who] were doing this—but we’re seeing more and more small-to-medium size operators establish produced water pits and produced water recycling facilities,” Smith said. Some will build a network of pits, some with fresh water, some with produced water, and send a mix of those to a third pit in preparation for treatment before being used for frac’ing.

Smith credits lower oil prices with some of the shift to reuse of produced water. “At $100 per barrel for oil, I’m not so sure that you really care what you’re paying for water; you’re just wanting to drill and frac as many wells as you can. But with lower prices on this commodity, now we’ve got a situation where every penny counts. If we can install recycle facilities where we can [treat] this water, we can use it over and over again.”

Pruitt pointed out that this turns produced water from a liability (costly to dispose of) into an asset (not only not requiring disposal costs, but saving the cost of buying fresh water).

Overseas Creativity

This boom in treating water has not only inspired local entrepreneurs like Smith, it has made the United States, and the Permian in particular, more visible to overseas innovators.

Sofi Filtration, Ltd., based in Espoo, Finland, is opening an office in Houston, with a sharp eye focused on West Texas.

Company CEO Ville Hakala says Sofi’s proprietary filtration system was developed for the mining industry in Finland and its environs. The system filters very fine particles from large streams of water. It is an “automatically self-cleaning water filter” that removes particles as small as one micron.

“It has to be where it doesn’t require disposable filter changes and it doesn’t require chemicals,” he said. The first system was installed in Finland in 2013 and has run successfully since then. The company did a full scale sales launch the following year.

They quickly began looking at ways to expand beyond underground mining—and the oil and gas sector was one that appeared particularly attractive.

Ironically, their first interest from the United States came from a major chemical firm that sent a representative to Finland to check out the technology. After a trial in 2014 the firm decided they were not ready to buy.

But the Houston-based representative liked the idea so much he quit the chemical company and asked Hakala if the two of them could work together to bring the filtration technology to the United States in some other way.

For a company seeking entry into the oil and gas sector, including the Permian Basin, Houston was a natural launching point. Hakala decided to spend the first three months of 2018 in Texas himself to establish a beachhead for the product.

With most companies innovating on the high tech side—Big Data and other computer-related advances—Hakala is proud that his product does not involve databases or even electricity.

“Often the innovation that is called innovation or development in the water world is related to IIoT or a higher level of automation.” Many of those are incremental more than new innovations, at least in the water sector, Hakala believes. “We are kind of proud,” he says, of the fact that this development is purely on the operations end. He also feels that 2018 is the right time to move into the produced water treatment sector.

“We just need to prove ourselves,” he says.

In the current water treatment market, that’s the mantra of just about any water recycling company. Various methods, chemicals, and companies are jockeying for position like thoroughbreds heading into the first turn.

The best news for those companies is that it appears indeed to be only the first turn—the track may get wide enough to accommodate all entrants as the flow of produced water—and possibly regulation—increases dramatically over the next few years.

Paul Wiseman is a freelance writer in Midland.