Things are bigger in Texas. Tex Thornton, an early 20th century oil well firefighter in the Lone Star State, strung together enough exploits to become, at least during his era, the biggest name in his daring trade.

by Bobby Weaver

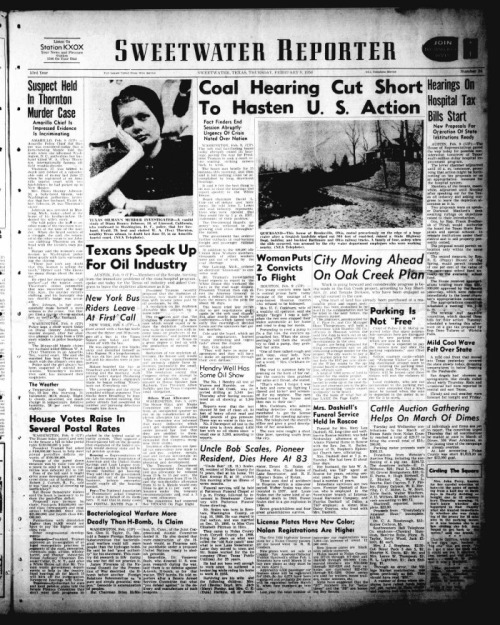

No oilfield occupation has the aura of romance and danger like that of oil well firefighting. It seems that every decade of the 20th century had its favorite hero of the genre. The late1950s through the 1990s featured Red Adair of Houston. Myron Kinley of Oklahoma dominated headlines during the 1930s on into the early1950s. But during the decade of the 1920s the daredevil fire fighting darling of the press was Tex Thornton of Amarillo.

Until the decade of the 1920s the traditional method of extinguishing oil well fires was to smother the blaze with steam and water. A battery of 20 or so steam boilers placed adjacent to the fire projected steam and water into the inferno until it was extinguished. The simple mechanics of an oil well fire is such that it requires a specific mixture of natural gas and oxygen for the fire to exist. The purpose of the steam is to decrease the amount of oxygen, which in turn causes the flame to die. That traditional method took a week or so of effort, which made it very expensive in terms of equipment and labor as well as in lost production.

Sometime prior to 1920 someone developed the concept of using a large explosion set off close to the wellhead, a tactic that would accomplish the same thing in a short period of time with little expense. There is some argument as to who exactly first accomplished the feat, but there are several contenders. Some say that a superintendent for Texaco named C.M. Chester first tried it in 1908 on a fire in Southeast Texas. Others claim that an oil well shooter named Ford Alexander accomplished it near Bakersfield, Calif., in 1913. But it is known that Tex Thornton managed to do it at Electra, Texas, in 1919. Regardless of who was first to try the new method of extinguishing oil well fires, the technique gradually caught on during the 1920s and Tex Thornton became one of its most publicized practitioners.

Ward Augustus Thornton was born in Mississippi on Oct. 9, 1891, but prior to his sixth birthday the Thorntons moved to Texas. The family settled at Goree in Knox County, about halfway between Wichita Falls and Abilene. When an oil boom developed at nearby Electra, young Thornton, at the tender age of 16, dropped out of school to answer the siren call of the oil patch. He dressed tools on rigs in that area for a couple of years before getting a job with a torpedo company as a well shooter. The company sent him to Ohio, where he trained as a shooter and acquired the name of “Tex,” which stuck with him for the rest of his life. Upon returning to Texas he began work for the U.S. Torpedo Company of Wichita Falls and shot wells throughout that north-central Texas area during the booms at Ranger, Burkburnett, Desdemona, and Breckenridge. It was during this period in 1919 that he shot out his first fire near Electra.

In 1920 the U.S. Torpedo Company moved him to the burgeoning oil development region around Amarillo as branch manager for the company’s Panhandle operation. The well shooting business was good in the Panhandle in the early 1920s and Tex soon gained the reputation as an expert well shooter. As early as 1922 he began getting serious about fire fighting, as evidenced by the occasion when he brought a well fire under control by devising an ingenious valving arrangement that shut the well in. Later, in 1924, he shot out a fire in Hutchinson County that had been blazing for a week. It was widely reported in the press that more than a thousand people gathered to watch the spectacle. He extinguished six blazes the following year.

In early1926 the Borger boom took off and so did the career of Tex Thornton. During the spring of 1927 a series of oil well catastrophes occurred in the Panhandle and Tex was in the midst of all of them. On April 11 a premature well shooting explosion shattered a derrick near Borger, killing three and badly injuring three more. Tex was on the scene and the newspapers lauded him as a hero for pulling the injured to safety. Before the hubbub surrounding that died down there was a major explosion and fire at a well within the townsite of Sanford about ten miles west of Borger in which eight were killed and five injured. The explosion happened about 8:30 in the morning of May 26 and by mid-afternoon Tex was at the scene. Two days later after having entered the blaze several times clad in an asbestos suit in search of bodies and to clear away debris, he shot the fire out.

Less than 24 hours later another well explosion and fire occurred just southeast of Borger. This time Tex tried the steam boiler method but it was unsuccessful so once again he donned his fast-becoming-legendary asbestos suit and entered the fire to place a charge. After the fire had raged for some 60 hours he shot it out before an audience of 3,000 people who had gathered to watch the spectacle. A week later, on June 9, there was yet another fire near Pampa that he put out in one day by utilizing the asbestos suit to enter the fire zone, where he closed a still intact valve which extinguished the blaze.

Putting out three oil well fires in a matter of two weeks with almost hour-by-hour press coverage made Tex an instant American hero. The national wire services picked up the story, dubbing him the “human salamander” and claiming that during his career he had extinguished more than 100 fires. Tex reveled in the glare of publicity and did little to discourage the wild claims appearing in the press. Besides, it brought in a lot of well shooting and fire fighting business from across Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.

Realizing the value of all the publicity, he made headlines the rest of the year by extinguishing several fires across the region while garnering praise from the Texas Railroad Commission members as having more nerve than Jack Dempsey and other national heroes of the day. Additionally he raced a modified Cadillac automobile in the 4th of July celebration races at Amarillo, took part in something called the Junkitkwick, sponsored by the Amarillo Automobile Association (in which he blew up several cars with nitrogylcerin), gave a fire fighting demonstration at the Tri-State Fair, and engaged in several other high profile headline-producing activities. Tex was a busy man during 1927.

Just as that burst of publicity began to subside he was called on to fight a fire at the Rachel #7 located near Corpus Christi. Tex decided to take the unprecedented step at that time of flying to the scene of the fire, but his plane was forced down by bad weather, which caused him to complete the journey by car. By the time he arrived the well had cratered, causing the drilling equipment to fall into the depression. He had a pipeline built from the Gulf to cool the pit area surrounding the fire with sea water but it was not until Feb. 6 that he was able to shoot the fire out. During preparations to shoot the massive blaze a San Antonio newspaperman borrowed Tex’s asbestos suit in order to get close up shots of the inferno. When the photographer collapsed from the heat Tex donned a spare suit and dragged him out of harm’s way. The event was recorded by another photographer and immediately the intrepid fire fighter was featured in full page spreads across the nation.

As time to shoot the fire approached, Tex discovered that he had underestimated the amount of nitro needed for the job. So he called Amarillo for more explosives. With nobody available to deliver the cargo, his wife assumed the responsibility and with the assistance of another lady they drove a carload of nitro the 700 miles to the scene of the fire. When the press broke that story it created another sensation and Mrs. Thornton received national acclaim for the feat. Later, during an interview about the incident, she declared, “Tex gets enough publicity without some other member of the family breaking into the newspapers.

“Besides,” she went on, “I don’t see why such a fuss should be made about it when I have been hauling nitro to and from the Panhandle field since we were married five years ago.” Evidently Tex was not the only member of the family becoming famous.

With all the excitement generated by his latest exploit, reporters flocked to Tex’s doorstep, where he did his best not to disappoint. That was when he told the story of how he once caught five nitro-loaded torpedoes as they were forced out of a well by gas pressure. A couple of years later he repeated the same story to another reporter with embellishments and went on to state that during his career he had done the same on a dozen or more occasions. Unfortunately there were no eyewitnesses to those feats of derring-do. In reality there is actually only one verified account of a shooter who caught a torpedo in such a fashion but it was not Mr. Thornton who accomplished the feat.

Following the spectacular events of the late 1920s Tex continued his well shooting and fire fighting activities with considerable success. During the mid-1930s, as business slowed to a crawl and West Texas became saddled with the tremendous drought of the dust bowl era, Tex branched out. In 1935 he made headlines again when he convinced the good people of Dalhart that he could make it rain by setting off explosives. Early in May of that year, after a couple of false starts, he sent explosives attached to a balloon aloft and set off a massive explosion. That night the area experienced a snow flurry that quickly turned a dirty reddish color, but no appreciable moisture developed.

Thornton continued his well shooting and fire fighting business and developed a considerable reputation in Amarillo for his civic work. In 1946 he made the claim that over the past 20 years he had extinguished more than 300 fires, a total that would amount to about one per month. However, the actual number will probably never be known because he kept such sketchy records. Amazingly, his impressive fire fighting activities, even if exaggerated, were done in addition to the regular work of shooting wells for production purposes. Of course there are the sidelines he tried, like rain making and even demolition work—such as bringing down a 70-foot brick incinerator that had become something of an eyesore in Amarillo.

On Sunday June 19, 1949, Tex left Amarillo for Farmington, N.M., to shoot a well. On Wednesday the 22nd he left Farmington and was on his way home when he stopped at a tavern in San Jon, N.M. In his usual flamboyant manner he bought rounds for everybody and after spending some time enjoying himself he left with a young couple who were hitchhiking across the country. Next morning his nude body was found on a blood-soaked bed in the Park Plaza Motel in Amarillo. In death as in life Tex went out in a blaze of sensational headlines. He would have liked that.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine.