We continue our coverage of the views of two highly respected industry observers as they comment on the recovery of 2017—a recovery that, if not “officially” in the works, is bound to unfold.

by Jesse Mullins

James Wicklund was speaking to the membership of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, and Wicklund, who is managing director of Energy Research at Credit Suisse, and a former petroleum engineer, shared a thought about how “things are going to be different this time” as the recovery of the oil and gas industry gains momentum in the coming year.

But first he remarked about that whole dicey business of “things being different”:

“I used to have a little baseball bat under my desk in a little holder, and I would tell people, “Whenever you hear me say, ‘It’s different this time,’ pick up this bat and beat the hell out of me.”

That got a laugh, of course, and Wicklund proceeded to disregard his own caveat and explain to his listeners HOW things will be different.

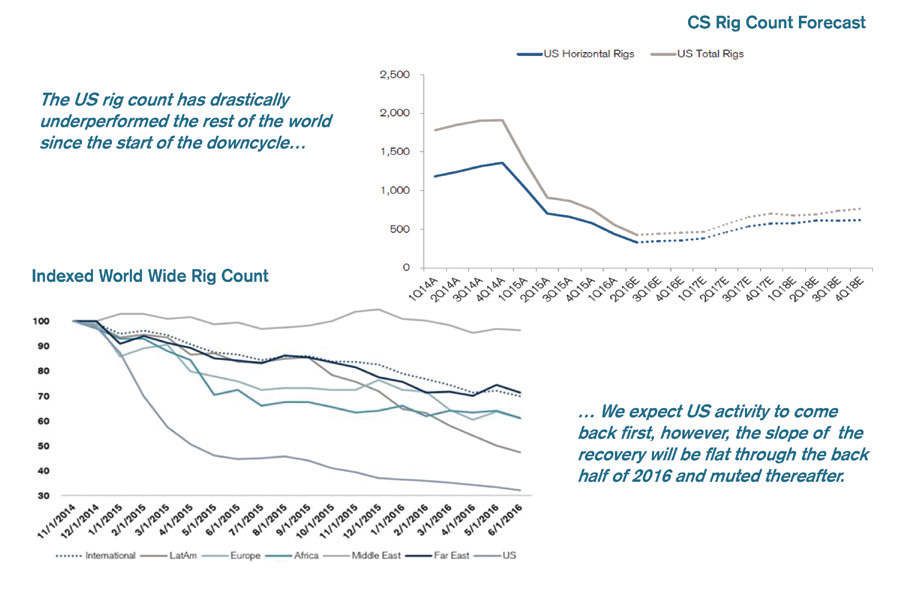

He gestured to a Powerpoint slide. (See accompanying graphic.)

“What you see here is our forecast for the future,” said Wicklund, spent 15 years in the energy industry before he went to financial services. “We are optimistic. This is notable for me, because for the last one-and-a-half to two years I have been the most negative analyst on the street. The bitch about being a negative analyst is, even if you’re right, nobody likes you. [laughter.] We’re trying to win people back, but you can tell by the slope of that line, we’re winning them back slowly and gradually. On the lower left you can see the indexed rig count. The rest of the world’s rig count has declined. The bottom line is the United States, and the top line is the Middle East, but you can see that the rest of the world has participated in this decline, though not nearly to the level of the United States.”

So, slow and gradual is the forecast for the Permian’s rebound, but another aspect, and one that Wicklund brought out, is that the rebound will be selective as well. More on that shortly.

We began this series by pointing out the inevitability of a rebound in any industry that follows a cyclical path.

What’s especially interesting about this balancing act is that not just that downturns produce upturns, and vice versa, but that the magnitude of a particular high or low tends to find its echo in a correspondingly pronounced move in the opposite direction.

Pendulum swings tend to have some reciprocity to them: a hard swing in one direction needs to be followed by a hard swing in the opposite direction. We shared in October a viewpoint published by The Motley Fool, which stated, earlier this year, that prolonged depression of crude oil prices means all-the-more pronounced upside once the upswing gets under way.

As Motley Fool reported:

“While this year’s global supply shortfall is projected to be relatively minor at 300,000 barrels per day, and easily covered by the glut of oil already on the market, it’s literally all downhill from there. According to Rystad, by 2017 declines will outstrip new supply by 1.2 million barrels with an even wider shortfall projected in 2018 before significantly worsening by 2020 given current projections.’That’s all coming as oil demand is expected to march higher by about one million barrels a day per year because of global economic growth.”

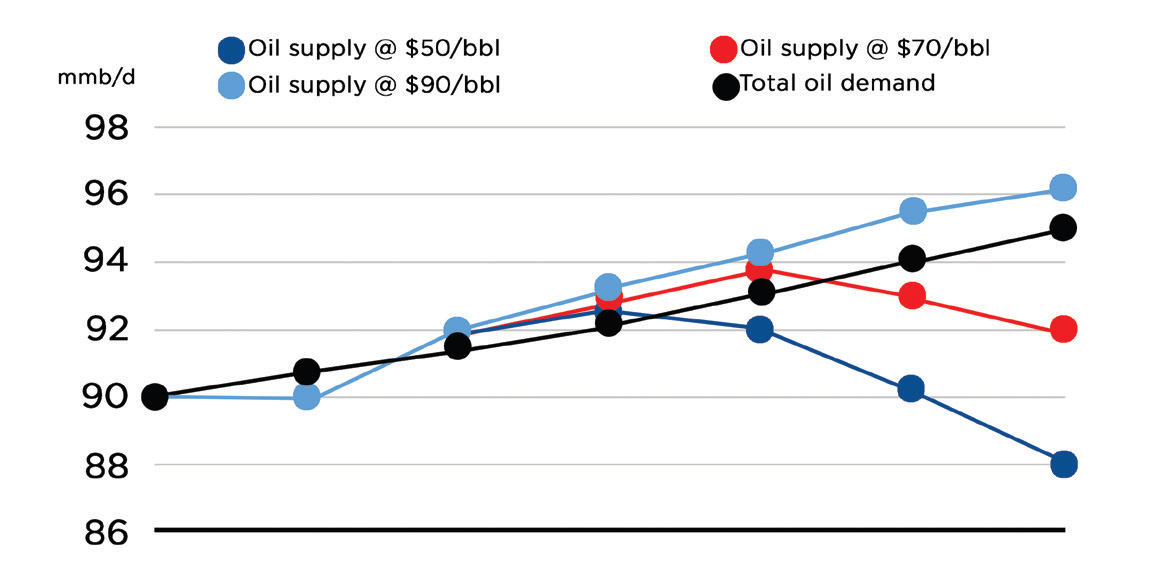

Motley Fool further underscored its point by referencing a chart prepared by offshore driller Transocean (see accompanying graphic).

On the graphic, Transocean takes an amalgam of estimates from Rystad and others, which is then run through three different oil price sensitives. The result is a potential significant shortfall in oil supplies should prices remain under $50 a barrel for the next three years.

As Motley Fool observed:

“One reason for this potential huge shortfall in supply is the high cost and long lead-time it takes for offshore projects to be developed. [To use offshore as an example], a major offshore project sanctioned today might not start producing until 2019. However, given where oil prices are right now, analysts expect only nine of the 232 pending projects to be given the green light this year because most of these projects aren’t economic. That lack of projects moving forward is causing Transocean to caution that its business might not see a pickup in the dayrates of offshore drilling rigs until the 2019 or 2020 timeframe because it will take the industry that long to get back up to speed.”

It is this kind of thinking that likely prompted Wicklund to remark, as he did, that the Permian will bounce back, and in strong fashion, but Houston will not be so favored by circumstances. “The offshore and deep water markets are basically dead for at least the next two years, okay? Chevron is going to be one of the biggest players in the Permian for the next five years. That’s because they’re not going to spend much money at all in deep water, because they’ve lost as much as they stand for a little while. They’re going to be focused on North America and, primarily, the Permian.”

But, as he said, things will be better here.

“Attrition—that’s a word that gets used a lot in our [market sector],” Wicklund said. “Attrition sounds like a permanent word; it’s not. It’s attrition until somebody throws capital at it. We actually think that pricing in the pressure pumping market is going to come back sooner than most people think. We think pricing and completions overall are going to start to come back in the first quarter of ’17. Since we’re sitting here in [fall] of ’16, that’s really not very far away. The completion end of the business, whether it’s sand, pressure pumping, completion tools, plugs, bowls, it doesn’t make any difference. All that business is going to be a much better business than the rig business going forward. This is just an example of frac intensity, if you will.”

Wicklund’s point about the rig business lagging behind the frac’ing business was simply this: rig efficiency has progressed so far that fewer rigs are needed to do the drilling that once required a heftier rig count.

“In January of ’14 the average production per rig in the Permian was about 180 barrels a day,” Wicklund said. “Today it’s 535. Not only that, but in January of ’14, the average drilling rig drilled 14 wells in a year. Today it’s 30. I can drill twice as many wells, and production is up a factor of three. The leading-edge wells in the Permian aren’t 535 barrels a day. The leading edge average is 1,100, and some of the better companies are reporting 1,700 barrels a day. It’s not just the Permian. The Niobrara has tripled, the Eagle Ford has doubled, and—because of the technology in the business, the increased completion intensity—we are going to be doing a great deal more with less. That’s the issue going forward.”

Wicklund had more to say—much more—and there’s not room to share it all here. But he concluded with this thought:

“We aren’t going to go back to 1,600 rigs. In fact, I don’t think we’re going to go back to 1,000 rigs in the next several years. If you go back to 1,000 to 1,200 rigs in the next two years, you almost guarantee that you’ll see $27 oil in ’18 or ’19. Efficiency and return on capital trumps growth. Business will get better, and you guys will lead. It’s not the 80’s, and it’s not 2009, but it’s still going to be good. And better.”

Our other observer whom we have quoted at length in this series, Karr Ingham, is equally bullish on the idea of a Basin upturn.

Regardless of how chaotic our recent economic times have been in oil and gas, the true picture is something that could actually be described as a very ordered process, according to Ingham, an Amarillo-based oil and gas economist.

“When you go back and look at what global supply and demand were doing in advance of price downturn, it’s not very difficult to see why this occurred, because the global supply curve went above the global demand curve and it stayed that way. As a matter of fact, it’s still there,” Ingham said. “That’s a recipe for price decline. It doesn’t matter what your wishes are, it doesn’t matter how quickly we all wish it might have corrected itself. Until it does, we shouldn’t expect prices to be significantly higher than they are now. This has to be accomplished through this set of processes. Supply goes down because you drill [only] 25 percent as many wells as you did when activity levels were high, but the fact that you did [drill all those wells in strong times] means all of these negative occurrences come as well. People lose jobs, companies go under, economies suffer. But, again, this is a very ordered process with the marketplace trying to get us from where we are to where we need to be.

“I’ve said it many times: we always look at this from the producer’s standpoint because that’s what we are, we’re a producing state, and the Permian is a producing region. That’s what matters here, but markets simply do not exist to serve the producer of anything. They exist to serve the consumer of whatever it is that’s being produced. We would be hard pressed to argue, would we not, that the consumer has not been very well served by this set of events. They were actually being well served by $120 crude oil and $4 gasoline. They didn’t know it, and they certainly didn’t think it, and they wouldn’t believe it today if you told them, but what that was doing, of course, was setting them up for what has occurred now, which is what? Price is going down, much more affordable energy, but more importantly than that, the establishment of a long term, affordable, abundant supply of energy for literally decades to come.”

Whether one calls that an “invisible hand,” or whether one chalks it up to just plain cause-and-effect, the results are the same. The market tends to serve the marketplace.

Ingham continued. “The hysteria we saw in the early part of the decade to the 2000s, where prices were going up [because of the supposed] inability to meet the rising global demand of the future and all the calamities that this was supposedly going to cause—that hysteria has vanished. Ain’t nobody talking about that now, thank goodness. This is going to be a globe that demands a lot of energy for these decades in the immediate future, and the Permian is sitting right in the middle of it. That has become one of the most important production regions on the globe. That’s the reason primarily that I think the Basin and the general economy there has a bright future.

“It’s astounding to think of the role that the Permian is going to play and has played, quite frankly, in the global energy scenario. I’m proud of it. I’m proud of Texas, I’m proud of the United States, I’m proud of the Permian, and I don’t want me to lose sight of that. I guess I don’t want everybody else to lose sight of these broader, fantastic occurrences, and the Permian has just been right in the middle of all of that.”

Watch for next month’s issue when we conclude this series with “The Results You’ve Been Waiting For: Election Implications 2017.”

Coming in State of Oil:

January 2017: The Results You’ve Been Waiting For

What the Election Means for the Basin. For more than a year, industry observers have said that the answers—for Texas and New Mexico, anyway—will not crystalize anytime before the general election. January will mark the first opportunity we’ll have to dissect the voting results of Nov. 8, 2016. We’ll have coverage of the implications not just of the Presidential election but the legislative restructuring of both the Senate and the House. And we bring to a close our four-part analysis of this brave new energy world we inhabit. In this issue, with the election behind, we’ll be able to make our sharpest prognostications yet. Where to from here? You’ll know what the Permian’s best minds have to say.

ADDENDA

“The land rig market, and if there’s any people in the land rig business in here I’m sorry, but there are some issues in this, and we’re going to talk about it. The rig count just broke 500 for the first time in a while. That’s after falling form 1,925 rigs less than two years ago. The problem is, we have a whole lot of rigs, and these things are designed to last 20 years. 75% of the rigs that have one back to work are tier 1 rigs, and that’s good, but of the rigs available to work just two years ago, [inaudible 00:03:21], utilization’s still only 16%. If you’re in the rig business, or you sell things to rigs, that is going to be the most challenged market going forward. Pressure pumping, however, is different. You have all heard about frack intensity, and completion intensity, and what it’s doing for the market. The pressure pumping market is gonna be the first one to come back.

Wicklund