Click here to listen to the Audio verison of this story!

Regardless of the exact status of environmental regulations, the oil and gas industry is working toward getting cleaner. Drilling and production activities often create material that’s more wasted than wanted, and methods for dealing with that are getting cleaner and safer. And in some cases, they’re turning trash into treasure, as with extracting minerals from produced water.

With the changes in Washington since the November elections, many in the industry are weighing the regulatory relief promised and enacted by the new president and his administration. For Permian-based companies working with solid and liquid waste disposal, those changes may be minimal, because here, the states of Texas and New Mexico oversee most of those rules, and for them it’s been business as usual since November.

The Rules Rule

Still, said Milestone Environmental Services’ EVP of Energy Waste, Richard Leaper, changes are coming in both states—and for his company they are welcome. With disposal sites in Texas and one in New Mexico, Leaper is uniquely able to compare the two, and he says both are “moving in the right direction” regarding waste disposal regulations.

New Mexico is known for being more environmentally focused than Texas, but Leaper says Milestone strives to go beyond regulatory minimums anyway, so there’s little issue for the company whichever side of the state line they’re on.

Of both states, he said, “They’re modernizing rules. I think they’re being more mindful and protective of the environment, but they’re also looking at and upholding the interests of the industry, where there’s certain economic interests and social license to operate. They do a good balancing act, but particularly in Texas those rules were very dated and they needed to be modernized.”

In the Lone Star State, Leaper said waste disposal rules had not been updated since the 1980s. Technology has changed and so have common views of environmental responsibility. While new Texas rules have not taken effect yet, he is pleased to see updates on the way into use.

Securing the Solids

Milestone’s Advanced Protective Technologies involve protecting the water table under a landfill with five impenetrable layers. In addition, there are groundwater monitoring wells encircling the facility, along with leachate collection systems. The types and thicknesses of the layers exceed Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) standards, he said.

Working up from the bottom, he explained that the base (first of five) layer is a geo-synthetic liner that is a more reliably impermeable substitute for the RRC-required natural clay.

Next is a secondary 60 mm thick HDPE liner, about 2 1/2 inches thick.

Third is “a geonet, which is a composite layer that functions as our leak detection system.”

“And then on top of that there’s another HDPE liner. This liner is the primary since it’s on top. Above that is another geonet layer which functions as leak detection. Our pipeline leachate collection system is on top of that, which continuously dewaters the landfill cell.”

Leaper said it’s about being as secure as possible. “There’s lots of redundancy there. It’s protecting the community. It’s protecting our customers in the industry as well from future liability.”

Because Milestone’s disposal business is confined to landfill-related solids and the injection of small amounts of unrecyclable liquid slurries, a “tiny proportion” of what’s injected by SWD operators, they have not been affected by injection restrictions related to seismic activity. And the fact that new Permian wells may be producing higher water-to-oil ratios is also not a problem.

The company’s main waste streams involve drilling cuttings and associated fluids, and production and maintenance waste, with the latter’s portion growing notably in recent months. As one might imagine, production and waste streams are more consistent, growing steadily as more wells are drilled, and remaining active regardless of the price of oil. Drill cuttings, on the other hand, fluctuate with prices and markets.

Still, the production side is growing for two main reasons, said Leaper. “We’re seeing a greater proportion of waste coming into off-site disposal, basically through greater awareness from our customers as well as enforcement of the new rules from the Railroad Commission.”

In 2024 they added a facility in Glasscock County near Stanton and collocated with its already existing slurry injection operation. Leaper said that expansion is less about an increase in waste than about “some areas in the Permian that ([had] lacked infrastructure in the past.”

Capturing Carbon

About three years ago Milestone decided to expand its services to new markets, adding carbon capture and storage (CCS) to its business. Leaper explained, “The idea there is to expand our services to heavy industrial customers or CO2 emitters that are looking to reduce their carbon footprint and reduce their emissions to CCS. Essentially, we’re taking our core competency of slurry injection in oil and gas and applying it to injection of liquefied CO2 in the CCS space.”

They are now in the process of developing centralized CCS injection hubs to serve multiple industrial CO2 emitters, connected by a pipeline network. One location is in the Midland Basin and one is in the Delaware Basin. Once they gather sufficient client commitments, Leaper said, “The plan is to start those up, probably anytime between now and 2030.”

Additional hubs could come later, located on the U.S. Gulf Coast, in the Midwest, and in the Rocky Mountain states. Much planning and capital expenditure is involved in this, which is why it has already been in the works for three years, he said.

Bitter to Sweet: Alternatives to SWD for Produced Water

It’s not that there aren’t a lot of alternatives to saltwater disposal (SWD) for produced water. The problem is that most of them, at least right now, are too costly or can’t be scaled up, or both. For more than 20 years SWD has been the produced water coping mechanism because it was the winner in the economics battle.

But now, the times, they are a-changin’, to quote Mr. Dylan, who was not referring to SWDs. Disposal-related seismic activity coupled with a general feeling that all that water—and at least some of its contents—should somehow be useful is pushing producers and the marketplace alike to look for better alternatives. And product developers are burning the midnight oil to make the alternatives not only cost-effective, but maybe even profitable.

Two people behind a new technology currently being field tested by Double Eagle offered some insight into how the mineral capture part can work.

David Clouse is managing director of EIC Rose Rock, a venture capital fund that invests in many startup energy projects, focusing on digitalization, sustainability, and emerging energy technologies. They have invested in Element3, which has developed a system that has been proven in Midland to capture, even profitably, lithium and produce battery-grade lithium carbonate from low-concentration oil and gas wastewater. This lithium can be sold into the marketplace. EIC Rose Rock feels Element3’s method is a key component of a domestic critical mineral supply chain. Hood Whitson is CEO and founder of Element3.

With Permian seismic activity getting increasing attention, Clouse said upstream and midstream executives he’s talked to, who invest in the EIC Rose Rock fund, see produced water as among their biggest issues. Listening to their concerns means EIC “as a fund and as technology searchers and innovators can go find our solutions to these problems.”

Clouse found issues with most current procedures, including evaporation and simply piping the water beyond the Permian, both of which in effect waste the water resource that could be employed in agriculture, river restoration, and other industries to relieve stress on the water table. And, in his view, they leave valuable minerals in the waste stream that is still injected underground.

Permian Jungle?

Treating the water to that extent is possible now. “We can use filters, we can use membranes, all sorts of technologies to get there. You can get to the point where you can use this for agriculture.

“We could turn the Permian Basin back into a Permian jungle [as it was in the Permian geological period that fostered the oil currently being produced]. He sees the region as a “huge carbon sink.” Which is great, but the regulatory environment will have to change significantly before that can happen. Decisions must be made, monitored, and enforced about what constitutes water being clean enough for what purpose. That would be especially critical for food agriculture or municipal use.

How to make that work and to get industry buy-in is the big question.

Efficiently pulling out valuable minerals like iodine, lithium, magnesium, calcium, and others, thereby getting a relatively clean water stream for industrial, agriculture, or something else, is a key step, Clouse said. “Then the revenues that come from selling that fresh water and the lithium and the iodine and all the other things that you’re pulling out is going to help pay for that higher processing.” That would make it more cost-beneficial to do the higher level of treatment than to just dump the water into an SWD.

Element3’s Whitson says his company focuses on lithium. “We really founded the company on the premise that we need secure domestic supplies of critical minerals, and with a trillion gallons of oil and gas wastewater, it’s one of our nation’s largest untapped natural resources,” he said. With that aim they looked for technology that could effectively collect the “high volumes and low concentrations that we see in the lithium feedstock in produced water” to make that process commercially viable.

How does this work?

Whitson explained, “We have an extraction media that we’ve developed that is very selective for lithium and is able to extract the lithium from raw produced water. We don’t have to sit on the backside of a concentrated stream. We can sit right in the produced water flow—it’s in a midstream system—and selectively extract the lithium. We then can also process that lithium all the way down into finished battery grade lithium carbonate.”

While lithium is a headliner in energy transition due to its prevalence in battery use, Whitson pointed out that it goes far beyond just batteries for Teslas. He listed everything from national defense systems to nuclear energy to “Gorilla Glass on your iPhone,” among lithium’s general uses.

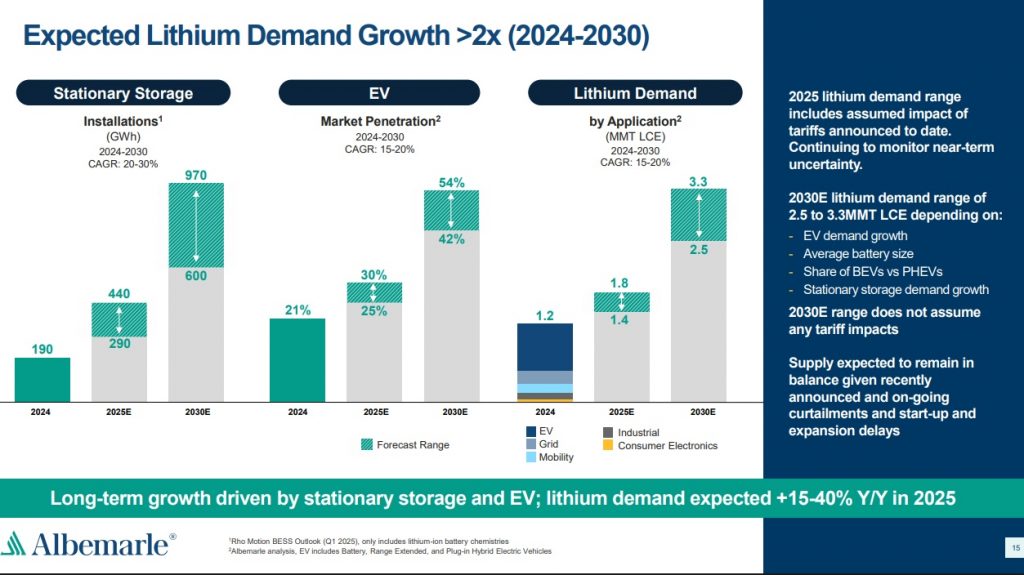

One might ask whether the market price of lithium is always going to make it a profitable sale, or even a sale at all. For that, Whitson holds a longer view. Healizes that lithium’s price is highly manipulated by international markets, and is currently very low, “But,” he said, “the growth of lithium demand is just extraordinary. We need to more than double the amount of lithium that will be produced by the year 2030.” He added, “We’re going to have to create more lithium in the next five years than we have in the previous 60, globally.”

To that end, Whitson said Element3 has long-term contracts with buyers across several industries. And Clouse agreed that securing a domestic supply chain is part of current national strategies.

Where are we now?

The system is currently being tested in the Midland Basin at a Double Eagle Energy Holdings, IV LLC subsidiary’s recycling facility. With that test’s success, Element3 is planning to build a lithium extraction plant in the southern Midland Basin. As for the schedule, “We’re aiming to deploy our first commercial plants by the end of the year and begin small-scale commercial production.” Whitson said.

A longtime contributor to PB Oil and Gas Magazine, Paul Wiseman is an energy industry freelance writer.