Wherever Wheels are Rolling… on ice or mud or snow… the name that’s known is carbon black. Where the rubber meets the road. Just another essential product brought to the world by the fine folks in oil and gas.

There are places in West Texas, especially areas in close proximity to gasoline refineries, where you might notice clusters of equipment and buildings that—beyond expelling small plumes of steam-like emissions containing little or no particulate matter—are very unassuming. Unless you took the time to read the sign on the gate to the facility that indicated it was the carbon black plant of the such and such a carbon company, you would more than likely never guess its purpose. It was not always that way.

There are places in West Texas, especially areas in close proximity to gasoline refineries, where you might notice clusters of equipment and buildings that—beyond expelling small plumes of steam-like emissions containing little or no particulate matter—are very unassuming. Unless you took the time to read the sign on the gate to the facility that indicated it was the carbon black plant of the such and such a carbon company, you would more than likely never guess its purpose. It was not always that way.

Carbon black produced by the oil and gas industry is one of those little-known-but-necessary products essential to a modern lifestyle. Without it the wearing capability of the rubber in automobile tires would have the approximate life span of a teenager’s crush on the latest rock star. Carbon black production, perhaps greater than any other aspect of the oil and gas industry, has evolved over time from a stereotypical smoke-belching air-polluting monster into an ecologically friendly business serving a vital industrial need. How all that came about is a fascinating story.

The production of carbon black dates back thousands of years to the time of early Chinese and Egyptian civilizations, when soot was collected from smoldering wood fires to be mixed with oils to pigment the ink used in the writing they invented. During the Middle Ages, the large scale production of paper in Europe demanded an increased use of carbon black for ink, which in turn gradually turned its production into something of a cottage industry. By the mid 1700s production of the black material utilizing the same ancient methodology was begun in North America where it was known as “lamp black.” Following the discovery of the first Pennsylvania oil wells in the 1850s, natural gas began to replace the traditional wood fires to produce the material on a larger more industrial scale and by the 1870s it assumed the name “carbon black.”

The ability to use a petroleum-based material to produce carbon black gave the potential to manufacture the product on a large scale. Despite those production capabilities, the manufacture of the material remained low, primarily because its use was confined to ink, dye products in paint, and other limited applications. All that changed beginning in 1915 due to the influence of the burgeoning automobile industry. One of the problems associated with cars of that era was that the rubber in their tires did not wear well. Then it was discovered that the addition of carbon black to the rubber used in tire manufacture extended its wear capabilities as well as greatly reducing the heat build up. By the end of WWI in 1919, tires with a carbon black additive were being sold in the millions and the demand for carbon black used in tire production was soaring.

Texas with its massive petroleum production was a logical place for the growing industry to develop. However, there was significant opposition against using the state’s natural gas for carbon black production. In 1920 the Texas Railroad Commission ruled that use of natural gas to produce carbon black was a direct violation of state laws concerning the conservation of oil and gas. That policy led to a prolonged and bitter political battle between those who claimed that the use of natural gas needed to make carbon black would rob citizens of gas needed for domestic consumption and those who said there was plenty of gas available to serve both markets.

The struggle went on for several years until 1923, when a law was passed allowing the limited use of natural gas to manufacture carbon black in Texas. That same year the Columbian Carbon Black Products Company built the state’s first carbon black plant near Breckenridge in Stephens County. Permission to operate was granted utilizing only casinghead gas, the residue from gasoline plants, and other sources where the gas could not be made readily available for residential use. That first plant was quickly followed by two more in the same general area. Three years later, on March 11, 1926, the Railroad Commission granted the Phillips Petroleum Company permission to build the fourth plant in the state near their new gasoline plant just north of Borger in Hutchinson County in the midst the newly discovered Panhandle Field.

The carbon black industry was a little slower arriving in the Permian Basin. The first plant built in the Basin was near Big Lake in Reagan County early in 1930, to be followed closely by one near Hobbs, N.M., later that same year. It was not until 1937 that Cabot Carbon Company built another plant at Wickett a few miles west of Monahans. At that point in time Texas boasted 40 carbon black plants that were producing 82 percent of the nation’s carbon black. Some 33 of the Texas plants were located in the Panhandle, mostly in the Borger/Pampa area, which dominated the industry in the state by producing 90 percent of the Texas output.

At the beginning of the industry in Texas and for the following three decades carbon black was produced by the “channel” method. This method utilizes only natural gas for the feedstock. The gas is burned in “hot houses” and as the black accumulates in moving channel irons, which are simply H shaped metal beams, it is scraped off into bins and transported by screw conveyors to storage areas. The inability to separate the resulting dust from the hot house vent gases caused those facilities to spew large dark clouds of black dust into the atmosphere. As a consequence, those plants were usually built in isolated regions, away from populated areas, where the manufacturers provided adjacent housing for their employees similar in nature to the traditional oilfield camps scattered across West Texas.

With the advent of WWII, carbon black was declared a critical product needed for the war effort. As a result, the government’s War Production Board built new carbon black plants across the nation, owned by the government but operated by the various carbon companies. A number of those new plants were located in the Permian Basin at locations including Hobbs and Eunice, N.M., as well as Seagraves, Kermit, Goldsmith, North Cowden, Midland, and various other places in the region. The largest of those, reputed to be the largest in the world, was one about six or eight miles west of Odessa. Although workers in the plants were allowed deferments from military service due to their work being considered vital to the war effort, few of them took advantage of the offer. Consequently many women were hired as operators in carbon facilities across the state for the duration of the war.

Beginning in 1946, shortly after the war’s end, the government began to divest itself of the various carbon black facilities through a series of auctions. At that time there were more than 40 carbon black plants in Texas. Of that number, 27 were in the Panhandle, which still dominated the industry in the state, although there were 13 located in the Permian Basin, including the one at Hobbs and two at Eunice, which made that region’s part in the industry a sizeable one.

By around 1950 the Permian Basin was fully invested in the carbon black business, with the former government plants scattered across the region now privately owned. For example, Cabot Carbon Company had bought the one at Hobbs while Columbian Carbon owned those at Eunice and Seagraves. Phillips purchased the one at Goldsmith that used the discharged gas from its refinery located there, while United Carbon Company bought the one at Midland. Also the Sid Richardson Company won the bid on the huge one west of Odessa. Meanwhile a plant was dismantled in Kansas and moved to Big Spring where it was rebuilt adjacent to the Cosden refinery just east of that city. A few were simply taken out of service and dismantled, along with their associated camps, although that was rare.

Despite best efforts toward installing various types of smoke arresters and filters in those old channel type plants, they were still noted for putting vast amounts of pollutants into the atmosphere. There was little difficulty identifying their location due to the plumes of dense black smoke all of them vented to the atmosphere. Eye witness accounts from the early 1950s declared that the smoke from the large plant just west of Odessa could be seen from as far away as 40 miles. That was an issue that the industry constantly struggled with while using the channel method of production.

Workers in the channel plants were furnished change rooms where they left street clothes and donned work clothes which were always black by the end of shift change. Despite the company-supplied shower rooms, personal dust protection devices, and using various ways to keep the black off their bodies, such as smearing vasoline on exposed parts of their bodies to keep the powder from direct contact with their skin, it was difficult to get totally clean. Most of the employees stated that in warm weather when they sweated it was not uncommon for the black residue to seep out of their pores and stain their bed linens. Despite those obvious problematic conditions a number of medical studies have shown few long-term serious respiratory effects of carbon black exposure to workers, unlike the medical effects of coal dust, to which it has often been compared.

By the mid-1950s, though, the industry began to change over to an oil furnace method of carbon black production which solved almost all of the pollutant problems. In the oil furnace process the feedstock is oil, which is combusted and contained in an enclosed furnace situation, which negates the discharge of almost all the dust to the atmosphere. That improvement, combined with the ability to produce more variations in particle size, created a much higher quality product which spelled the demise of the outmoded channel black process. By the end of the 1960s almost all the channel plants in the Permian Basin were either modified to the new process or had been abandoned. The last to go was the big Sid Richardson plant west of Odessa, which ceased operation in 1971.

Thus, with all the technological change over time, the carbon black industry portion of the oil and gas industry has continued to be a little known but important element. That is also why today when you drive past a carbon black plant in West Texas you would probably not even know it was there, beyond some sign outside the gate to the facility. The only discernable discharge from the plant would be that small plume of whitish steam-like smoke that contains little or no particulate material going into the atmosphere.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to PB Oil and Gas Magazine. His humor column, “Oil Patch Tales,” also appears in every issue.

Bobby Weaver is a regular contributor to PB Oil and Gas Magazine. His humor column, “Oil Patch Tales,” also appears in every issue.

Carbon black

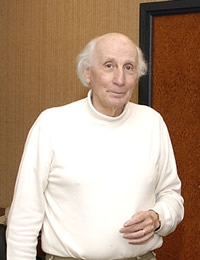

Wikipedia identifies four scientists as pioneers in the development of carbon black as an industrial product. Two shown here are Jean-Baptiste Donnet (left), who passed away in 2014, was a French chemist noted as a pioneer in the surface chemistry of carbon black and as a founder of the Upper Alsace University, and Joseph C. Krejci (right), who was a chemical engineering associate at the PhillipsCarbon Black Research facility in Borger, Texas. He died in 1991. He is known for his work in developing the oil furnace production process for carbon black. Not shown: William B. Wiegand was a vice president of Columbian Carbon Co., known for his pioneering work on carbon black technology. Wiegand studied carbon black’s reinforcing effect on rubber, and proposed that the effect arises due to forces acting at the interface between the carbon black and the surrounding elastomer matrix. He too was a pioneer in developing the furnace method for producing carbon black. Siegfried Wolff, retired since 1992, was a Degussa chemist noted for first recognizing the potential of using silica in tire treads to reduce rolling resistance. At Degussa he also worked in research and development of carbon black.